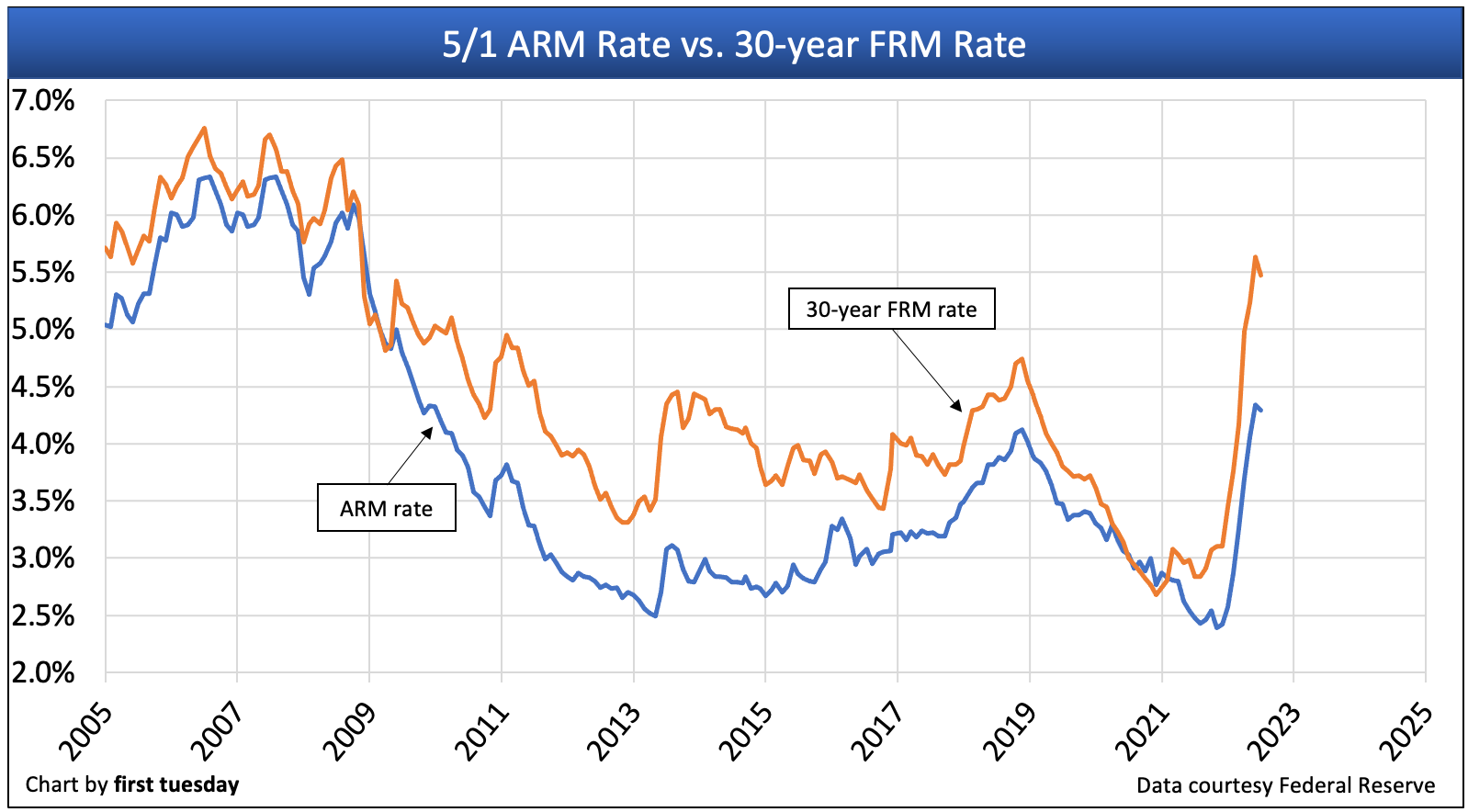

After skyrocketing in the first half of 2022, the average adjustable rate mortgage (ARM) rate fell back slightly to an average rate of 4.29% in July 2022, up significantly from 2.48% a year earlier. ARM rates have increased as a direct result of the Federal Reserve’s (the Fed’s) action to raise short-term rates to combat high inflation. Similarly, the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage (FRM) rate has jumped from historic lows in 2022, averaging 5.47% in July 2022, up from 2.84% a year earlier.

The average ARM rate is still below the average 30-year FRM rate. This makes riskier ARM products more appealing to homebuyers seeking to regain purchasing power as prices continue to increase on top of rising interest rates. Therefore, ARM use has received a boost in 2022 — injecting instability into the housing market.

But ARM rates won’t remain below FRMs for much longer in 2022. The reason? ARM rates are directly tied to the Fed’s benchmark rate, which the Fed has signaled it will continue to increase in 2022. Thus, when the Fed raises rates, ARM rates rise an equal amount. In contrast, FRM rates are heavily influenced by the bond market, which tends to accept lower long-term yields during times of economic uncertainty. As the undeclared 2022 recession intensifies in the months ahead, expect the bond market to keep FRM rates from rising faster than ARM rates. Thus, an inversion in rates is likely in the months ahead, which will slash homebuyer appeal of ARMs instantly.

Updated August 11, 2022. Original copy released April 2014.

Chart 1

Chart update 08/11/22

| | Jul 2020 | Jun 2020 | Jul 2019 |

| Average 5/1 ARM rate | 4.29% | 4.34% | 2.48% |

| Average 30-year FRM rate | 5.47% | 5.63% | 2.84% |

ARM rates rise from bottom

ARM rates peaked in 2006 at just over 6%. ARM use (the ratio of ARMs to all other residential mortgage loans) at the time was extremely elevated: three out of every four mortgages originated as ARMs, a recipe of disaster for the future housing market.

The rate is tied to a specified index that varies based on market factors. On adjustment, the new ARM rate equals the yield on the index specified in the ARM note plus the lender’s profit margin. Common indices used to periodically adjust the ARM rate include the:

- Treasury Securities average yield – one-year constant maturity;

- Cost of Funds;

- London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR);

- 3-month Treasury bill;

- 6-month Treasury bill; and

- 12-month Treasury bill.

ARMs are riskier than FRMs because the rate reset often results in substantially higher payments, and payment shock. This was experienced on a wide scale during the Millennium Boom as payments rose beyond homebuyers’ ability to pay. California’s 2008-2009 foreclosure crisis was driven in large part by these rate resets. The mortgage market is nearly fully recovered from the foreclosure crisis, seven years later in 2016.

Further, new underwriting standards (the qualified mortgage rules) require ARMs to be underwritten at the maximum allowable interest rate after five years from the date of the first payment. These new rules attempt to mitigate the risk of payment shock, which will work if the homebuyer takes out the ARM with the reset rate in mind rather than the more appealing teaser rate. [12 Code of Federal Regulations 1026.43(c)(2)]

So, are ARMs ever beneficial to homebuyers? ARMs do work well for seasoned, short-term investors who plan to sell within the initial lower-rate period. But owner-occupant homebuyers are advised to stay far away.

ARM use follows buyer purchasing power

When FRMs are available to homebuyers at reasonable rates, well-informed homebuyers choose FRMs over much riskier ARMs. However, when other market pressures are at work, even well-informed homebuyers find themselves considering the more risky ARM option.

This is because ARM use is tied inescapably to buyer purchasing power. As FRM rates rise, less of the monthly mortgage payment for which a homebuyer qualifies is applied to the principal. Thus, homebuyers cannot afford to buy at the same price they were able to a year earlier. Today’s spread between ARM and 30-year FRM rates is inverted, with ARM rates actually higher than FRM rates.

Likewise, when home prices rise more quickly than the rate of consumer price inflation (CPI) (as they did during the Millennium Boom and more recently during the 2013 year of the speculator), homebuyers are unable to qualify for the same amount of house as they used to.

This is where ARMs come in. Homebuyers turn to ARMs to increase their purchasing power, as the initial interest rate allows more money to be applied to principal. This allows homebuyers to afford a more expensive home. A quick fix, but a poor one in the long run.

Similarly, ARM use declines when FRM rates and prices are low. This occurred in 2009 at the tail end of the recession, when ARM use bottomed at almost zero.

The past year has seen a difference between ARM and FRM average rates too small to sway many homebuyers into considering the risks of taking out an ARM. It won’t be un until FRM rates rise again — not likely to occur until 2022-2023 — that ARM use began to rise.

Prior to 2014, mortgage rates had been on a steady decline since 1980. This downward trend enabled lenders and agents to encourage homebuyers to “just refinance” out of their resetting ARMs. However, the next two to three decades will bring a slow tide of rising mortgage rates. Thus, ARMs have the potential to be more dangerous for homebuyers in years to come than in recent memory.