Why this matters: Current uncertainty comes from a unique balancing act done by the Fed to both reign in consumer inflation and bring down high interest rates. For real estate agents and brokers, both concerns affect clientele. High mortgage rates suppress turnover and discourage changes while rising consumer costs, hiring freezes and insufficient construction push buyers to the sidelines.

Federal funds and cautious steps forward

The Federal Reserve (the Fed) uses a variety of financial devices to meet their congressionally-set goals of full employment and stable economic growth. One such device is their benchmark rate, the Federal Funds rate, more commonly called the overnight rate.

The Fed sets a range in overnight rates which apply to lending and borrowing between banks, including the Federal Reserve lending, which presently is 3.75% to 4.00%. The rate is set to induce or restrain levels of short-term borrowing in the banking system for funds banks lend to customers.

During periods of business recession, the Fed drops the Federal Funds rate to encourage more borrowing by banks and in turn their customers. Thus, more capital investment and consumer spending, and, in time, more jobs. During times of economic excess – boom times – the Fed raises their benchmark rate to inhibit lending and borrowing activity to temper the growth in capital investment, rising wages and consumer spending.

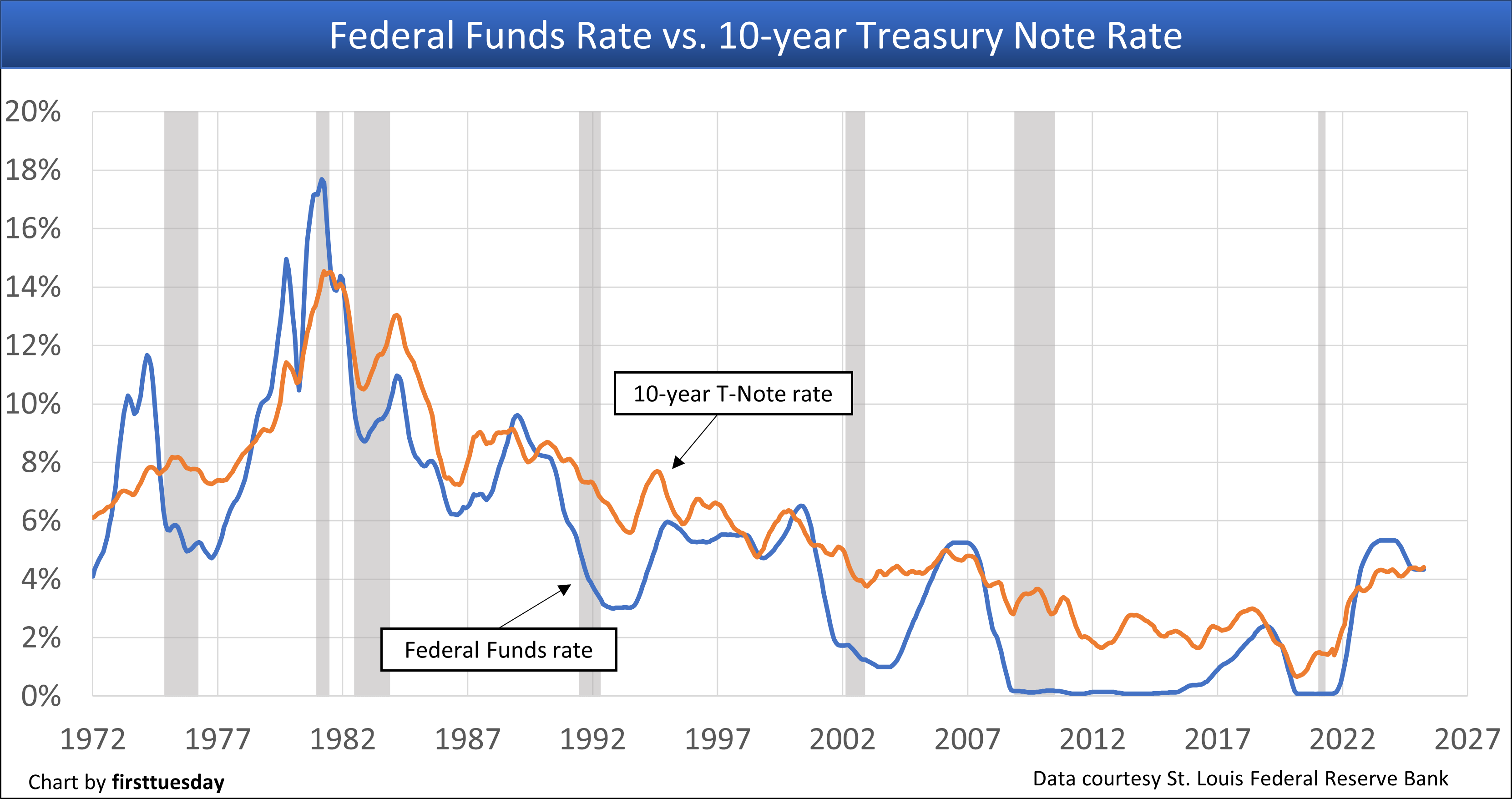

Chart updated November 7, 2025.

Chart update 11/7/25

Oct 2025 | Sep 2025 | Oct 2024 | |

| Federal Funds rate | 4.09% | 4.22% | 4.83% |

| 10-yr T-Note rate | 4.06% | 4.12% | 4.10% |

The Fed’s monetary policy at work

The Federal Reserve’s (the Fed’s) goals are to maintain through their influence:

- stable consumer pricing, not asset pricing;

- maximum employment without consumer inflation; and

- moderate long-term interest rates.

The Fed’s main concern is to keep wages and inflation from overheating the economy by using a monetary device to control banking operations called the Federal Funds rate. This is the rate charged on overnight funds lent between banks and to banks by the Fed. Based on the Fed’s rate plus a spread for losses and profit margin, banks lend funds to businesses and consumers to provide short-term finance for their purchase of goods and services.

When the Federal Funds rate, also known as the short-term rate, increases, the cost of borrowing by banks increases and is passed on to consumers who, in turn, reduce their borrowing and thus spending. When the Federal Funds rate is lowered, banks are motivated to borrow as consumers are willing to borrow at the lower rate permitted by the Fed funds rate. As a result of Fed Funds rate activity, banks tend to lend with greater or lesser frequency to businesses and individuals based on the resulting lower or higher rates.

Long-term rates move up or down based on the perception of bond market investors about the level of success the Fed achieves fighting inflation – or preventing deflation – in wages and consumer goods and services.

When the Fed’s inflation fight becomes aggressive, producing an inversion of the yield curve, investors perceive a recessionary period is ahead with fewer investment opportunities. In response, investors pile into notes and bonds as a safe haven, which causes long-term rates to decline.

As seen in the chart above, recessions (marked by the gray bars on the chart) coincide with decreases in the Fed Funds rate. Specifically, when the economy is about to enter a recessionary period, the Fed decreases their benchmark rate, making funds cheaper to borrow for banks and in turn consumers. This injects stability into the economy and lessens the depth of a recession.

On the economy entering into the recovery portion of a business cycle, the Fed gradually increases the Federal Funds rate to allow for growth in employment without a growth in inflation. This rate increase is the Fed’s method for putting a lid on the boiling pot of an over-heated economy — evidenced by rapidly increasing asset prices and consumer inflation.

If the pot boils over into economic excess, the recession that follows is long and hard — as most recently experienced in the Great Recession of 2008. That recession and following recovery were the longest such events since the Great Depression. It was the consequence of the wild, untamed decades of deregulating financial market activities culminating with the Millennium Boom, insufficient fiscal stimulus and 2010 congressional re-regulation for the long term.

The link between Federal Funds, T-Notes and FRM rates

A glance at the rate comparison chart above suggests to the casual observer that the Federal Funds rate and 10-year Treasury note rate might somehow be linked. But what is the connection? And what connection to ARM or FRM rates exist?

The first property owners affected by Fed rate movement are those whose properties are encumbered by ARMs. Each movement in the Fed’s short-term rate directly triggers a two-step mechanism to alter the note rate on an adjustable rate mortgage (ARM).

As the first step, any movement in the Fed’s short-term rate alters figures in short-term rate indices. ARM note rate adjustments are tied to the figures in one of these indices. As the second step, the property owner’s ARM note rate adjusts an amount equal to the movement in the index figures, limited to range-of-change restrictions in the ARM note.

These owners see their monthly payments increase or decrease after the Fed rate moves. The only limitations on ARM rate changes are ARM note provisions setting the time period for an adjustment, and ceiling and floor rate ranges for each adjustment and over the life of the ARM.

Rates for fixed rate mortgages (FRMs) are indirectly and belatedly affected by the Fed rate’s short-term rate activity. For a connection to the Fed rate, an FRM analysis is necessary.

The setting of the FRM rate at origination, fixed for the life of the FRM, is tied to the 10-year Treasury note (10-year T-Note), not the Fed Fund rate. The 30-year FRM note rate in normal economic times was set prior to 2013 roughly at a 1.5% spread above the 10-year T-Note rate. This rate spread for consumer-purpose mortgages has varied up to 3% since 2013 and is around 2.25% going into the recession underway in 2025.

This mortgage rate spread is classified as a risk premium received by the mortgage holder for anticipated:

- losses on a default by the property owner, a risk not present in the 10-year T-Note; and

- devaluation of the mortgage principal balance as long-term rates trend higher.

10-year T-Notes are purchased by bond market investors looking for a long-term safe place to park their money at a rate which anticipates the effect of future Fed activity to control long-term inflation levels. In times of protracted uncertainty for private investment, investors from around the world pour excess funds into 10-year T-Notes—as occurred in the first half of 2020 at the outset of the global 2020 recession. This surge in demand for bond investments increases the price of the 10-year T-Notes while decreasing the rate of yield—the interest rate earned on T-Notes. In turn, the 30-year FRM rate declines for new originations.

Now comes the interesting part. When a recovery period gets underway, the Fed initially raises their Fed Fund rate to commence a routine monetary (money supply) adjustment to fine-tune the national economy. In doing so, the Fed heads off what the Fed anticipates as future excesses in consumer inflation and wage increases due to growth in the national economy. This monetary activity instantly attracts the attention of 10-year T-Note investors.

Soon, investors in the 10-year T-Note pull their funds and re-direct the money into investment opportunities which will profit from a growing economy as anticipated by the Fed. As a direct result of these T-Note withdrawals, the 10-year T-Note rate rises as the U.S. economy heads into an expansion.

Since the FRM rate is set based on the 10-year T-Note rate, FRM rates on origination directly rise and fall with the path taken by 10-year T-Note rate. Conclusion: The Fed fights inflation and bond investors hunt for investment opportunities at the same time in an expanding economy – until:

- the Fed ramps up the Fed Fund rate to aggressively fight perceived excessive future consumer inflation; and

- investors quickly return their money to the safe haven of 10-year T-Notes.

Thus, long-term T-Note rates drop and, in turn, drive down the rate on origination of FRMs. Buyers borrow more with their same income, which attracts sellers, and real estate prices start to rise.

Related article: