California per capita income continued to grow in 2019. Statewide, income in 2019 grew 4.5% over the prior year, a slower pace than the 5.2% annual increase experienced in 2018. This pace of increase follows a pattern of minimal increase over the past decade. The number of homebuyers in a market stems directly from employment income, which, along with interest rates, determines buyer purchasing power.

Home value increases are unsustainable when they exceed an area’s average rate of income growth. Here in California, annual gains in home prices outstripped wage growth for years before prices began to level off in 2018. In 2020, home prices have gone the complete opposite of jobs, the result of historically low interest rates and an imbalance of homebuyer demand with inventory.

With 1.5 million jobs still lost due to the 2020 recession as of October 2020, and still more individuals who have seen their incomes reduced, expect to see the annual per capita income gains of the last decade reverse course when 2020 reports are released. The decline in home prices will follow soon after.

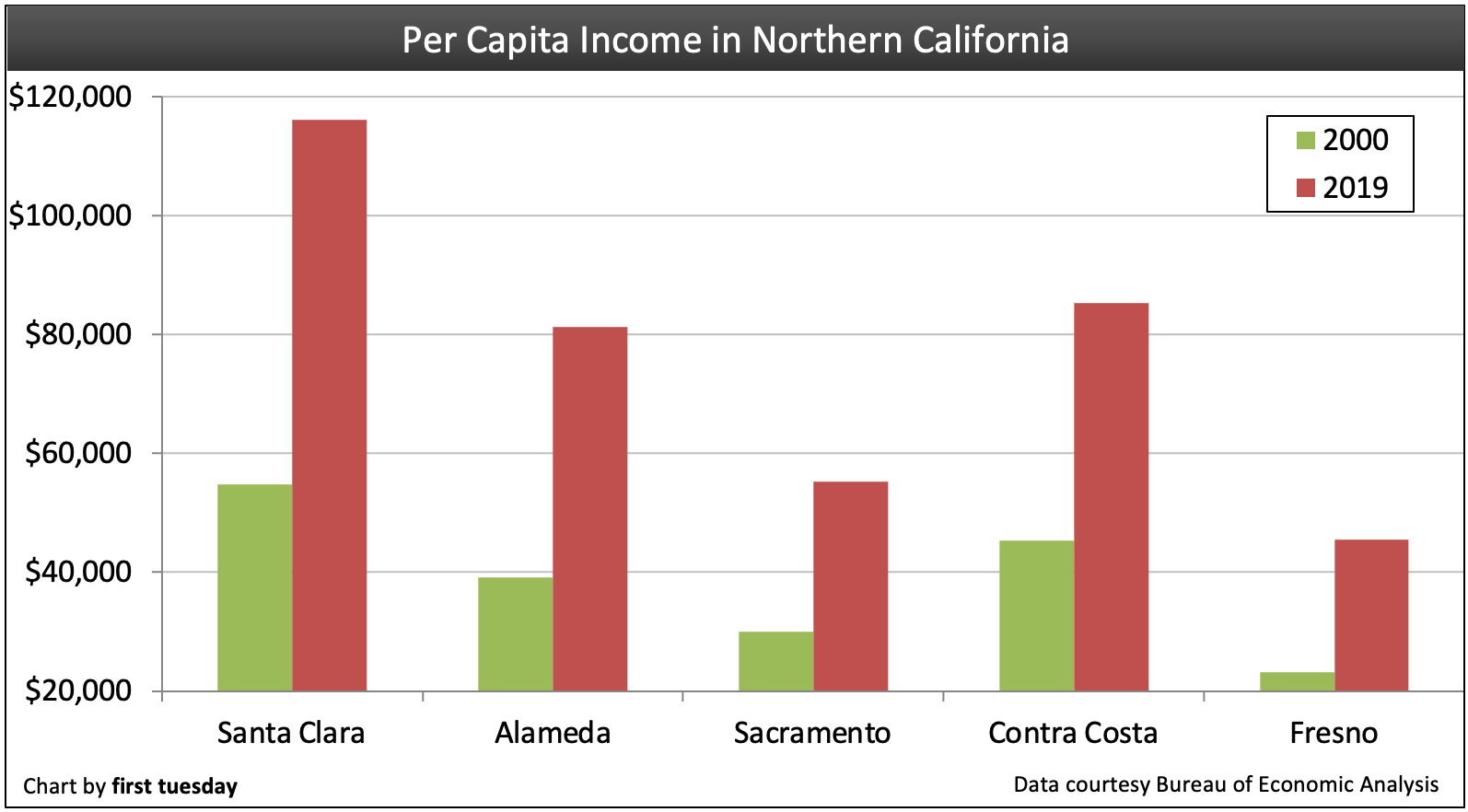

See the charts below to find out how California’s largest counties measure up.

For more detailed analyses of individual counties, visit first tuesday’s Regional housing indicators page.

Updated December 16, 2020. Original copy posted October 2011.

Chart update 12/16/20

| Los Angeles | San Bernardino | Riverside | Orange | San Diego | |

| 2000 | $30,000 | $22,800 | $24,400 | $38,100 | $33,800 |

| 2019 | $65,100 | $42,000 | $42,400 | $71,700 | $63,700 |

Chart update 12/16/20

| Santa Clara | Alameda | Sacramento | Contra Costa | Fresno | |

| 2000 | $54,700 | $39,100 | $30,000 | $45,600 | $23,100 |

| 2019 | $116,000 | $81,200 | $55,300 | $85,300 | $45,500 |

Data courtesy of the U.S. Census Bureau

This article is the first in a two-part series. For further analysis, including specific charts on age and education by county, see Age and education in the golden state.

The above charts track the net annual income per capita for the five largest counties in Southern California (SoCal) and Northern California (NorCal). Together, these charts present the ten most populated counties statewide. Dollar amounts are not adjusted for inflation.

Your gain from local demographic information

Success as a real estate professional depends upon one’s ability to develop expertise in a specific type of real estate service and cater to a specific type of clientele. This clientele may consist of older homeowners looking to relocate to a comfortable retirement, or may be mostly first-time homebuyers. Or maybe you cater to investors looking for nonresidential space or developers in need of parcels for construction.

The brokers and agents most likely to succeed are those most intimately familiar with the nature of both their clientele and locally-available real estate.

For proactive brokers and agents with healthy interests in local data, the extensive and detailed demographic information released every year by the U.S. Census Bureau is a valuable tool. By examining this information, you will learn the real estate related attributes of your area’s population and anticipate future population-driven real estate sales, leasing and lending trends. As the real estate recovery progresses on its bumpy road past 2007’s peak employment levels (a milestone reached in mid-2014), and California’s population continues to age, once-proud suburban regions are likely to diminish and formerly shunned cities will benefit from increased population density, personal wealth and construction.

In the first decade of the 21st century, Riverside County’s population grew faster and in larger numbers than any other county in the state, adding 644,000 people. This growth proved unsustainable (as was the past decade’s violent population growth in the Central Valley). Other areas, like Los Angeles County, registered slightly slower rates of growth which are likely to continue for the long term, as the City of Los Angeles is a population center capable of supporting a measured increase in residents, unlike the Inland Empire or Central Valley.

Related articles:

For the practicing real estate broker and agent, however, broad trends in population change are merely the tip of the iceberg. To cater to the local real estate needs of clients, brokers within each locale need the ability to anticipate client needs even before they are addressed by the client.

Such agent foresight requires specific local data about demographic attributes. Perhaps the most relevant of these statistics are those relating to income, age and education as shown on the charts accompanying this article series.

Analysis and application

These charts present demographic information on the five most populous counties in SoCal and NorCal, alongside the data for the state as a whole. On a broad scale, it is unsurprisingly apparent California became slightly better educated, older and wealthier since 2000. Keep in mind, however, that the slight, nominal increase in personal wealth is largely attributable to inflation, not the real (post-inflation) income growth which is needed to improve one’s standard of living.

Related article:

More interesting are the ways in which these data sets present the idiosyncratic elements that make each county’s population unique. While all of California’s counties have had population changes in recent years, and each continues to transform even now, progress has not been unified from county to county.

Brokers and agents who use these charted census data will improve their understanding of the community in which they work, or would like to work. If ever there was a time to consider relocating your real estate business, it is now.

Different age groups, educational tiers and income classes have different real estate needs. Homebuyers and sellers in separate communities often pay remarkable different levels of brokerage fees for substantially the same service, depending on the influence of each area’s trade association on industry-wide fee arrangements.

Also, the work done by the real estate agent to market and sell a low-tier suburban home to a first-time homebuyer is often more challenging than the work undertaken by a commercial property broker negotiating with a buyer for a large-scale income property, even though it tends to pay dramatically less. Just think of the property investigations and disclosures that are made, or not made, in each field.

That said, the brokers who have the most success are those who specialize in a type of service most demanded by the local population. For instance, San Bernardino’s general lack of college education, widespread low income and younger population is certain to lead to greater demand for rentals and low-priced single-family residences (SFRs) than the older and wealthier populations of Contra Costa or Orange County. The contrasts are often even starker from city to city, as between Palos Verdes and Bakersfield or Monterey and Salinas.

Census data can also provide a picture of a county’s likely future development. During the 2000s, Orange County’s per capita income rose 33%, and its median age rose by 9%: the greatest rise in age of any of the ten counties displayed. Signs indicate that Orange County is feeling the effects of the aging Baby Boomer generation as the Boomers pull their wealth out of retirement accounts, sell off suburban homesteads and seek a commodious spot to retire to in coastal southern California.

Related article:

It all comes back to earning power

The homebuyer’s ability to maintain his property and pay a mortgage or rent is the crucial factor determining the property he lives in. Per capita income measures the average income per person in a population center, and sets the average amount of money spent by members of the community.

While income figures fail to show how accumulated wealth is spread across the population, per capita income is a valuable measure of a community’s financial ability to purchase one or another tier of property. As such, personal income and its rate of change move the price point paid for property within a given area. Combined with trends in local employment data, it is possible to extrapolate the likely price that segments of the local population will pay to buy or rent within a county.

Related article:

A community’s ability to buy real estate – particularly a home – or even rent, is hampered by every jobless individual who can no longer make a monthly mortgage or rent payment. In 2020, jobs were lost across the state at an unprecedented rate, and have been slow to return. Statewide, the number of jobs held was down 1.4 million from a year earlier as of October 2020. These job losses impacted every corner of the state, including regions with relatively high incomes.

Income is the product both of the number of people employed and the type of work in which they are employed: the population’s high levels of education in Alameda and Santa Clara counties mean that the workers there are more likely to be qualified for high-paying white collar positions, making per capita income less dependent on unemployment.

Lucrative computer industries are the prime drivers of wealth in certain sectors of California, especially in counties surrounding the Bay area, like Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Jose and San Francisco. Farther south, different industries dominate. In wealthy Orange County, the top industries include leisure and hospitality (13% of wage-earners), perhaps reflecting that county’s high number of retirees, while farm labor is practically nonexistent. San Diego, which has seen an upsurge in per capita income over the last decade, continues to see dramatic growth in medicine (especially physical therapy and medical science) and information security.

For brokers and agents, personal wealth determines both the type of client and the type of property they buy and own. Remember that like calls to like; real estate professionals in most of NorCal or Orange County will need to dress for success and do thorough research if they want to impress the highly-educated white-collar professionals who live in their areas.

Those who live in the Central Valley or Inland Empire, on the other hand, may find home sales activity painfully lethargic for the upcoming years, unless they turn to working with equity purchase (EP) foreclosures, real estate owned properties (REOs) and short sales. On the other hand, these same lower-income communities were the sites of the most vigorous development in the boom years, and they retain that potential for explosive (and unsustainable) growth when economic recovery begins once again.

Related article series: