Many not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) protestors and the neighbors they seek to convince believe the construction of a low-income housing project reduces neighboring home values, but they’d be wrong (in most cases).

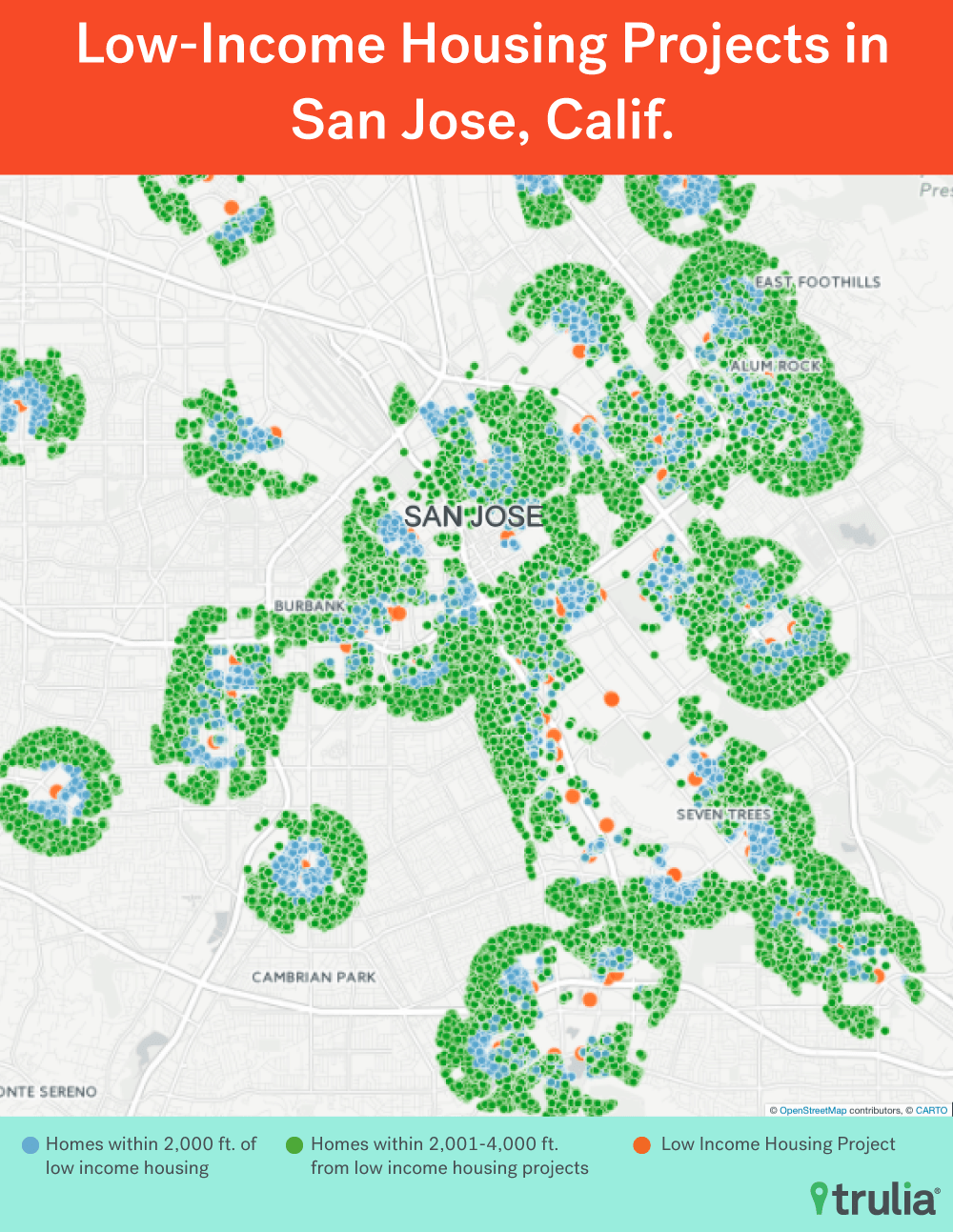

Trulia analyzed the change in home values before and after low-income housing projects were built nearby. To avoid accounting for the dramatic, unrelated changes in home values that occurred after the Millennium Boom burst, Trulia limited their study to home values near low-income housing projects built between 1996-2006. They looked at homes within 2,000 feet of new low-income housing projects and homes between 2,000 and 4,000 feet from new low-income housing. For both distances, their findings showed no significant variance in the pace of home value increase following each project’s completion.

Of the 20 metropolitan areas studied across the nation, the only place where low-income housing had a measurably negative impact on nearby home values was in Boston, Massachusetts. In California, the study showed no difference in the pace of home value increase before and after low-income housing was built.

Once caveat to this study: only the 20 “least affordable” metropolitan areas in the U.S. were included. In California, this includes:

- Los Angeles;

- Oakland;

- Orange County;

- Riverside;

- Sacramento;

- San Diego;

- San Francisco;

- San Jose; and

- Ventura.

Therefore, California metros where housing costs are more in line with resident incomes, such as Fresno and Bakersfield, may not necessarily follow the trend.

The secret to keeping low-income housing from impacting home values

To prevent future negative impacts to home values from low-income housing, we can look at the city that bucked the trend: Boston.

Trulia economists speculate the reason for the negative impact there was due to the concentration of low-income housing projects. Several low-income housing projects were built in close proximity to each other, and certain neighborhoods were quickly associated with the low-income housing projects. This both hurt each neighborhood’s reputation and left little room for future development.

On the other hand, areas where low-income housing is spread out and more seamlessly integrated into neighborhoods fare much better. Take a look at Trulia’s map of San Jose, where each orange dot represents a low-income housing project:

This thinking is somewhat in line with the defensible space concept, which transformed urban development in the 1970s and 1980s. The concept’s creator theorized that — compared to typical low-income high-rises — several smaller low-income housing units, scattered throughout the existing community, reduces crime and increases surrounding home values. The concept proved fruitful, and cities that adapted this model did see a decrease in crime and a positive impact on home values, according to the National Housing Institute.

However, critics correctly observed cities that adopted the defensible space concept saw a significant reduction in the number of low-income units in their metro area.

It’s now accepted that, while low-income housing structure and architecture matter, what’s most important in reducing crime (and thus keeping nearby home values from suffering) is screening for the appropriate types of tenants. Each development needs to have a balanced mix of young families and older, childless families. That’s because projects with disproportionately high numbers of children and teenagers see a higher crime rate, according to the urban affairs publication, Next City. There also needs to be a balanced mix of families on the low-income spectrum — grouping highly impoverished people together is a recipe for disaster. Rather, a mix of residents falling from the bottom to the top of the low- to moderate-income spectrum is more productive.

So how should current residents react when their local city council shares the possibility of a new low-income housing project? Ought they try to influence how the project will be built and implemented?

Absolutely, residents need to get involved in their community planning. But the appropriate response is not the typical one.

For many, the traditional NIMBY response is a no-brainer. But it’s not a real solution. NIMBYs end up pushing all of a metro area’s low-income developments into a single neighborhood, which perpetuates crime and poverty.

Another solution is inclusionary housing, in which a portion of a new development allocates a certain percentage of its units to low- or moderate-income housing. Inclusionary housing measures are funded by the government and executed by private developers.

Most of all, successful low-income housing is in the hands of local governments. For an example, see Fresno, where zero government enforcement of housing codes has contributed to some of the lowest home values in the state. Local officials need to enforce safe, habitable living conditions in low-income properties, otherwise landlords will inevitably allow properties to deteriorate.

Agents and brokers can help keep home values from deteriorating when low-income housing is introduced by getting involved in the planning process and attending local city council meetings.

Very good article. I confirmed these conclusions in 1989 during a visit to Chicago. Near my cousin’s home was a four building highrise. When we walked by, my cousin pointed at one building and asked if I noticed the difference. He explained that it was the subsidized building, while the others were market rate. Because subsidized tenants realized their good fortune to be in the building, good behavior was easy to enforce, as none wanted to lose such a good home. This confirms the article’s conclusion that the key to successful low income housing is seamless architectural integration and avoiding concentration [ghettos].