This article warns of the impending era of due-on-sale enforcement that will befall the real estate market in the approaching age of rising interest rates.

Interest rates — WWII to Reagan and back

At the dawn of America’s postwar economy, interest rates were at historic lows. In 1951, the 30-year fixed rate mortgage (FRM) hovered around 4%, as it did for most of that decade. The personal savings rate was also historically low.

Despite the fact that personal wealth was still recovering from the body blow of the Great Depression, jobs were in great abundance. The advent of the military-industrial complex Eisenhower so distrusted (WWII to Vietnam), coupled with the need to restore America’s crumbling infrastructure led to surging employment, booming gross domestic product (GDP) and a seemingly unquenchable demand for houses, goods and services.

By 1965, the constricted money supply set interest rates on a long upward trajectory, and inflation started to soar under the wartime economy. Almost a quarter of all the savings and loan associations (S&Ls) in California were in serious financial turmoil. The S&Ls had lent on anything to everyone during the booming early ‘60s, and had done so at rates that did not adequately cover the risk of future inflation, eventually causing their total demise by the early ‘90s.

The result was not unlike what we saw in 1991 and 2008. Foreclosures spread like wildfire, and rather than receiving a bailout, a large number of California-based S&Ls were allowed to collapse. Lenders were forced to acquire property by foreclosure, and lender insolvency ran rampant. Thus, merger upon merger occurred. Most often, mergers were induced by governmental pressure (and money) to keep weak lenders from going under or being taken over at greater expense to the government (sound familiar?).

Inflation, Boomers and interest rate uprisings

By the early 1970s the Baby Boomers had arrived and were setting the economy on fire. The Federal Reserve (the Fed) in those days was not as alert and proactive as our current Fed, allowing inflation to hit double digits, turning homeownership into a hedge against inflation-investments. In 1979, the new Fed Chairman promptly shut down the over-exuberant economy by raising short-term rates to 18% plus, on and off for two years before the Fed single handedly brought inflation under control.

Once this occurred, mortgage rates began a long and steady 30-year decline, until they reached the point of absolute zero that we see today. Today, we are right where we were at the end of WWII in terms of low interest rates and inflation, but not in terms of having come out of the recession as occurred by the end of that economic period. [For a comprehensive financial history of the U.S. real estate market spanning WWII to the present, see the first tuesday publication Real Estate Finance, Fifth edition, Chapters 1 and 2.]

Interest rates at the real bottom

Based on the current historically low 30-year FRM interest rate, many industry pundits have speculated about the future fluctuations of the interest rate and its effect on prices. The prevailing question in the press has been oversimplified and uninformed: will the interest rate go any lower? This query is typically accompanied by the seemingly eternal and intrinsically related refrain, when will prices increase? [For current real estate-related interest rate data, see the December 2011 first tuesday article, Current market rates.]

The simple answer to the first question is: no, rates cannot go any lower. This, of course, answers the second question in the negative, since prices will only increase if mortgage rates drop, (or production of goods and services increases beyond the rate of inflation).

Allow us, dear reader, to explain.

Although the current 30-year FRM interest rate hovers around 4%, the real interest rate is effectively zero. Thus it is impossible for the rate to go any lower, lest lenders start paying borrowers to accept their loan funds — a fantasy that is possible but highly improbable (called going negative by bankers).

In order to understand the reason why mortgage rates are now essentially zero, one must first grasp the concept of real vs. nominal interest rates — a fairly straightforward concept. Essentially, the nominal interest rate is the mortgage rate advertised by lenders, stated in the note and reported by the media. In theory, the nominal rate includes a premium rate sufficient to account for expected future consumer inflation.

In turn, the real rate of interest is the nominal interest rate minus the current rate of inflation. Since the core rate of inflation is currently 2%, the real interest rate of today’s 30-year FRM is 2%.

Editor’s note — The rate of inflation used for this analysis reflects the core rate of inflation, an adjusted index excluding food and energy prices, which are volatile and properly adjusted out of inflation calculations. The reason: commodities return to their mean-price level leaving little long-term effect on the core rate of consumer inflation. Evidence: Gasoline and copper prices are all over the place every few years, but your mechanic has been charging you $100 n hour since the ‘80s.

Additionally, the core rate of inflation is reported monthly and has fluctuated marginally above and below 2% for the past two decades. Thus, we use the 2% figure here for the sake of clarity and simplicity, acknowledging that it is the targeted level of inflation set by the Fed for their long-standing monetary policy. The same is true for the mortgage rate discussed in this article, which has marginally fallen below and risen above 4% for the past year or so and will most likely do so well through 2013.

The zero lower bound and the liquidity trap

But 2% is not zero, as we have claimed the effective rate on the 30-year FRM to be. This vestigial 2% is eaten up by two inexorable factors: the discount rate and the risk premium rate (to cover defaults) added to mortgages, a margin to assure profitability. The discount rate (the rate paid by lenders to borrow funds directly from the Fed) is currently at .75%, which puts the effective rate of return on a 30-year FRM at 1.25%. This just happens to be the approximate risk premium added to 30-year mortgages, as they are typically pegged at 1.4% or so higher than the 10-year Treasury note (T-note) in order to effectively capture investor dollars for mortgages that might otherwise be invested in “risk-free” government bonds.

The current real rate of return for the 10-year T-note runs just a few tenths of a percentage point above the core rate of inflation. This is due mainly to excessive world-wide currency risks which have driven the yield on the T-note down, the U.S. dollar being the safe haven delivering the real estate industry this benefit.

Thus, the real interest rate on the 30-year FRM is currently zero, offering only a high enough nominal yield for lenders and their investors to keep pace with inflation and retain their money’s purchasing power until they find themselves clear of this rippling global downturn.

It is axiomatic, dear reader. Just like bonds, mortgage rates operate in inverse proportion to prices. As rates go down, prices go up, and vice versa.

Since rates literally cannot go down, prices will not go up until the money supply is unleashed and consumers begin to spend. Although money in the form of loan funds is basically free, no one, especially lenders, is spending it — a phenomenon known as the liquidity trap.

In order for prices to rise any further, we must first pass through a full cycle of rising-then-falling interest rates. As inflation picks up, mainly due to the trillions of dollars of cash the Fed has injected into the private banking system since 2007, and as we gain more jobs into 2014-15, interest rates will be driven up by the Fed to withdraw excess liquidity (money) pumped-in to keep the economy from tanking.

The question is not if, but when — and by how much will interest rates rise to keep the economy from recovering at breakaway speed.

The due-on time bomb: be aware and ready

Now here is the rub. The fact that interest rates have bottomed-out and will begin increasing over the next several years is a paradigmatic game-changer for the real estate market. That includes you, our readers.

Since the interest rate spike of the 1980s, when rates peaked at 18%, interest rates have been on a steady decline, and have come to rest at a point beyond which they cannot go. An entire generation of homebuyers has become accustomed to not only low interest rates, but interest rates that have continuously gotten lower.

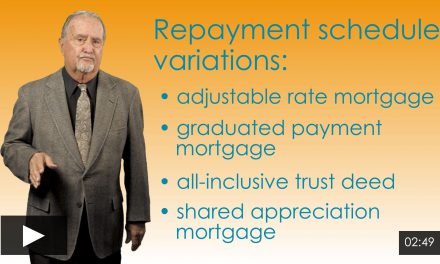

Thus, the notion of a double-digit interest rate on a 30-year FRM is unthinkable to most potential homebuyers. Aside from the negative implications that zero-bound rates carry for a recovering economy that depends on consumer confidence, a surge in the heretofore receding interest rate tide heralds the resurrection of a most insidious barrier to real estate transactions: enforcement of the due-on-sale clause. [For a comprehensive overview of the due-on-sale clause inherent in all trust deeds, see the March 2011 first tuesday article, The due-on-sale clause: barricading homeowners since ’82.]

Events to occupy a broker’s mind

Thus, while the housing market lingers in the purgatory of low interest rates and low prices, waiting for interest rates to begin their inevitable rise, there exists a due-on time bomb ticking silently just below the surface of real estate sales volume numbers. The bomb will not explode all at once but in slow motion, as rates will rise gradually with creeping inflation and as the employment rate picks up.

This calculus is well-known to brokers who arranged sales during the high interest rate period of 1977 to 1982, a period during which the due-on clause was held at bay by the courts and the strong-arm sheriff – until deregulation let the bears of Wall Street roam at will and build strength, gorging themselves on profits for the last 30 years.

However, once those who have been lucky enough to secure a mortgage at today’s low rates are ready to sell and interest rates have begun to rise (likely during a 2016-forward real estate boomlet), prospective buyers everywhere will be asking the same question that most did in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s: how can I assume the seller’s low-rate loan? At that moment, real estate brokers and agents will have to take the opportunity to educate their client buyers and sellers about the due-on-sale clause included in every trust deed.

Since most buyers in the near future have been raised on falling interest rates, they have had no occasion to learn the term due-on. Brokers have forgotten; agents have not been trained.

Dangerous assumptions

Buyers in the real estate market of the last 30 years would not be interested in assuming the seller’s loan, as they were almost always more likely to get a lower rate on a freshly originated loan.

The advent of Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO) scoring and the fears it engendered added to the lender’s dream of constantly rolling over mortgages to get origination fees (and prepayment penalties). In the off chance a real estate transaction took place which could trigger due-on enforcement, a lender would never exercise their right to call the loan; that would be insisting on making a new loan at a lower rate than the existing loan’s rate — something that will never happen as lenders have one goal only: profit. [For an analysis of the fallacy of FICO scoring, see the December 2011 first tuesday article, The FICO farce.]

As mortgage rates go up, as we have shown they will, lenders will not only pose a barrier to new deals, but they will also begin to call loans en masse on all “subject to” sales transactions, conduct creating high potential for another lender-instituted housing bust of a completely avoidable variety.

They will even sue brokers and agents in retaliation for assisting buyers and sellers in Wellenkamp-style loan assumptions, demanding payment of retroactive interest differential (RID) at the increased market rate over the note rate from the date of closing, a sum they cannot collect when they call the loan on discovery of the sale. [Wellenkamp v. BofA (1978) 21 C3d 943 (Disclosure: the legal editor of this publication was the attorney of record for the plaintiff in this case.)]

Who’s manning the ship?

What can be done to protect the housing market from the unbridled lender dominance instituted by the Garn-St. Germain Federal Depository Institutions Act of 1982 (Garn) and essentially ignored by lenders, brokers and principals ever since?

First, awareness of the deleterious effects of due-on enforcement (especially to a recovering economy and Multiple Listing Service (MLS) housing sales volume) must be developed amongst the professional gatekeepers of the real estate industry who have more at stake than padding their bottom line (read: brokers and agents who deal in real estate as their vocation).

This awareness must then coalesce into political action agitating for the repeal of Garn St. Germain due-on enforcement — for without repeal nothing can change. The momentum for such an action is already building with focus on mortgage lenders by elements of the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement. Do not ignore the increasing national consciousness that the successes of the 1% are now systemically integrated into the guts of our political system. [For more information real estate professional involvement in the OWS movement, see the October 2011 first tuesday article, Unions occupy Wall Street — where are the Realtors?]

Enforcement of the due-on sale clause is a prime example of such institutionalized avarice. It benefits no one but lenders to the detriment of society at large, no longer justified as serving any social good as it was portrayed before Congress 30 years ago.

Begin agitating for change now, before rates start rising — once the great boulder begins rolling again, you and your sales volume will get crushed.

Isnt there anyway to avoid Due On Sale? Trust? LLC? Or one of those corporations are people ideas?

Just a picky comment. Regarding your comment about Interest rates being inversely related to prices. That is not always correct (at least not in the historical data I have seen regarding California). There are times when interest rates and prices are rising at the same time. It is more about affordability, of which rates are only a part of the equation.

Coffee is for closers, only. :)

The two words “educate clients” made this a five star article for me. Also, due-on-sale clause is a new one.

Some of the buzz is a bit much, like using the word “calculus,” and agitating for “change” with an “occupy” element. Who is your audience? It would be better if you leave out the political charge which misses the calculus anyway, and talk to the rationale of the market savvy real estate professional.

Thanks for stirring the barrel.

If these clauses are legislated null and void, then the cost of borrowing will simply go up dramatically. Lenders, over the past 30 years, have suffered enormous losses as people refinanced their loans into lower rates. That’s just part of the deal; what hurt lenders on the way down, as interest rates fell — will benefit lenders on the way up, as interest rates rise.

Oh MY…I was not complaining,,,but my last posts reads that way…millions lose homes due to Fed crashing market…….those 5 million people vote. Vote job killers out !!!! Thats all,,,,, HAPPY SELLING !!!!!! Smiles !!!! 2012 is growing into an awesome year…Take care of family & friends !!!

Jeff, as I understand All new loans cannot charge a pre payment penalty. That is a huge saving, in the future if enough people complain loud enough, laws might change. Seeing millions lose their homes when this fed raised rates and crashed the markets on purpose. The Fed who is a group of overseas bankers. Just got rid of most of their competition. Bear Sterns and Lehman were competitors…they are gone. Yet the 14 OVER SEAS banks got 16 trillion from the US tax payer. Google search Federal reserve Audit 2011 then you will have a FULL PICTURE. Searh the CHARTER , Fed has no competiton, Per CONgress. These facts are NOT figured into published figures. Jeff I agree with you, Just saying those who pull the strings on the USA Checkbook make the rules. …..currently banks and insurance companies profit wildly. SMILES my friends,,we are through the worst of it. HAMP II will help stablize neighborhood values.