The middle class suffocates under taxes

Advances in the realm of economics don’t often make the news. But it’s possible you’ve heard of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century, the economics book that took the world by storm in 2014. If you haven’t heard of Piketty’s research, then you’ve certainly heard of its main topic: wealth inequality.

Piketty’s thesis is crisp: return on capital grows more quickly than economic growth. Drawing this out to its natural conclusion, individuals who inherit substantial wealth see their assets increase more quickly than those relying on wage increases. Thus, wealth inequality will continue to grow between:

- those who labor for a living (the debtor class); and

- those who rely on investments for a living (the rentier class)

– unless regulations are altered, most likely through changes in the tax code. Property tax and Inheritance tax quickly come to mind.

Most relevant to real estate is Piketty’s idea that members of the middle class are being taxed exorbitantly on their greatest source of wealth: their homes. Piketty points out that we tax property in the U.S. without respect to actual accrued wealth. Taxation is based on the face value of the property, instead of the amount of the owner’s home equity – their wealth and capacity to pay.

An illustration

Consider two people who each purchase a $500,000 home. One owner liquidates stock to pay cash for the home. The other person put 3.5% down and has a job to support payments on a $480,000 mortgage balance ($20,000 in equity).

Taxwise, both are treated the same, even though they have two very different wealth profiles – capacity. (The exception is of course the mortgage interest deduction, which the owner paying all cash is not privy to, but that issue is a different discussion.)

Compounding the inequality is the fact that wealthy households have many nest eggs, thus ensuring not all their eggs are in one basket. Middle-class Americans often only have a single nest egg: their homes. Matthew Yglesias, writing for Vox, puts it this way:

Historically speaking, real estate has been taxed more heavily than other kinds of wealth because you can’t hide a house or shift it to an offshore account in the Cayman Islands. In contrast, state and local governments lack the technical capacity to tax mobile wealth like stock portfolios.

Thus, there are checks put in place by local and federal governments that in one sense keep incomes of middle-class homeowners in check. For the rentier class, these rules are bulleted with loopholes that lawmakers refuse to acknowledge, much less close.

The critique

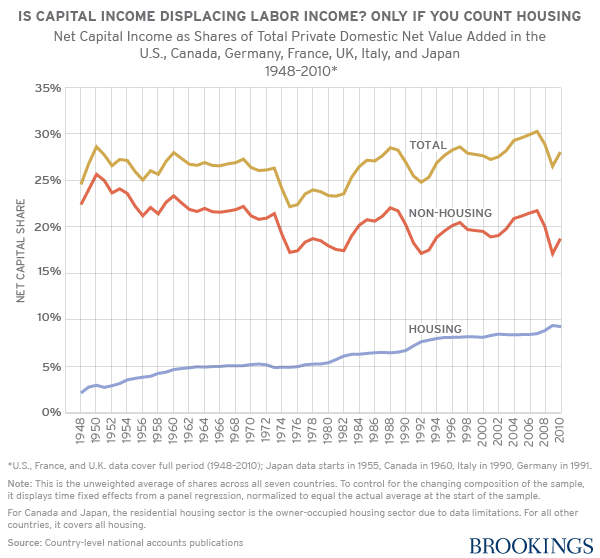

However, if you examine the growth wealth in capital – across the much of the world – over the past 60+ years, you’ll notice that most of this growth was actually seen in the housing sector. Take a look:

Source: Matthew Rognlie: Deciphering the fall and rise in the net capital share. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

In the chart above, you can see how property values have risen steadily as a share of total wealth over the past several decades. Other types of capital as a share of total wealth vary more wildly from year to year, but have actually declined slightly over this same time period.

This chart’s author, Matthew Rognlie, claims that Piketty’s analysis – which pits debtor against rentier in a competition for wealth that the rentier class continues to win – is flawed. Instead, Rognlie suggests we just forget about the rentier class, as their slice of the economy has no bearing on the rest of us, the 99%. As he says: “Observers concerned about the distribution of income should keep an eye on housing costs.”

The imbalance between home prices and wages

Indeed, housing costs have risen far more quickly than incomes in the past several years. Lenders and landlords alike recognize the ideal maximum a household should be spending on monthly rent (or mortgage payment) is roughly one-third of their monthly income. However, average housing costs are far beyond that in the areas where most of California’s residents live, at:

- 47% in Los Angeles;

- 41% in San Francisco;

- 40% in San Diego; and

- 36% in Riverside.

How have housing costs gotten so out of control? From 2000 to 2013, real income (that’s income after inflation) rose 4%. Real home prices rose an incredible 75% in California over the same period.

Related article:

As more households are pouring a bigger share of their incomes into housing costs, less money remains to be contributed to the consumer economy, or saved. The savings rate has declined, to only 4.6% at the end of 2014, down from a peak of over 12% in the 1970s before mortgage deregulation set in. Naturally, this makes saving up for a needed down payment problematic, suggesting no end is in sight to this vicious cycle.

The solution

So, how to fix this big ol’ economic mess we’ve gotten ourselves into?

If you ask Piketty, it starts with helping the middle class overcome their unequal tax burden. This means taxing property based on its equity and not on the property’s fair market value, a “simple” change to the tax code.

On the other hand, Rognlie suggests we tackle property values themselves. The most realistic way to do this is to alleviate situations where demand outstrips supply, as most often occurs in urban areas and especially California (Texas producing the opposite result).

Keeping up with housing demand in urban areas not only brings housing costs more in line with wages, but enhances the entire economy. For instance, employment in and around San Francisco has the potential to increase by 500% without the legal restraints of zoning on new construction, according to the Economist. To translate, a more vibrant economy and more housing means a higher homeownership rate and greater home sales volume. Further, local tax revenues from property and sales will greatly increase, allowing local governments to meet community demands for classic services.

To achieve this goal, it means changing zoning codes.

The obstacle facing both of these solutions is that money talks loudly, very loudly to the exclusion of the middle class. Those with money have stakes in keeping certain loopholes firmly in the tax code and in controlling their neighborhoods from competitive growth. These advocates for restrictive zoning are often referred to as NIMBYs (not in my backyard advocates). But it is the resulting rush in property prices made by restrictive zoning that controls the thinking of NIMBYs, not community needs.

One thing’s for certain: nothing will improve if we adhere to the status quo.

First, we need a shift in attitude. Placing the rentier and debtor class in competition won’t initiate change (the debtor class lacks the money needed for this type of distinctive transformation).

Instead, let’s work for the same end. Surely members of the rentier class don’t want to return to a world without a middle class — that would make for a pretty poor economy, and unstable protest movements to boot.

Once we get on the same page about financially healthy shelter needed by newcomer households, businesses and government agencies, we can begin to work toward a shift in policy. If you agree, you need to let your voice be heard by participating with members of your local city councils and planning commissions to affect density through zoning change:

…forgot to include – the advance of debt as control of the population. We are not permitted to get enough wages or any other source of money to be able to pay our bills and the expenses to give us the benefits applauded in all our anthems – U.S. songs and dances about our wonderful living in freedom and WOW equality!

Regulations only cause capitalism to buy its way out of them. Recommendations to continue the capitalist structure and to regulate it so it’s not so bad 1. recommends continuation of capital’s ownership of everything; 2. promotes zombie politics – resurrect what already didn’t work time after time. Capitalism is not a victimless crime. Go outside and look around.

Thanks for the insightful comments. There are so many flaws in this kind of thinking. Home equity is where the middle class keeps their money. Why not tax it more to try to help them out. what????

I agree that the idea of property taxes based upon the amount of equity in a home would be unfair to people of all income classes. Including those who have restrained their consumption in order to gain equity and who were not born with a chunk o f equity in their mouths.

The other idea of increasing the supply of housing seems more promising, Although NIMBYism is a problem there, I believe the overall issue would not necessarily be resistance by wealthier people in better neighborhoods to changes in zoning to allow much more affordable housing. Once again, regarding this also, opposition may not only come from wealthier quasi rentier types but from several segments of the population, including those who have labored hard to gain access to such areas,

I don’t agree with the sentiments expressed by some that there is nothing that should be done about the affordability crisis. Only that more thought be put into it.

I am confused. What is the goal here? To increase revenue for the state government? To take money from those with the good sense to manage it? What is proposed would drastically increase the property taxes for my 90 year old father who has the good sense to buy a home and NOT take cash out of it so he could retire without the burden of a house payment. He paid about $25,000 for the home, which is in the Silicon Valley, so you can take a wild guess at the price now. Certainly some change could and probably should be made to the property tax structure in California, but a wholesale change targeting equity seems punitive to a lot of people we should be protecting. The state’s income tax schedule is already so progressive it hits the middle class like a ton of bricks. By the way, what is so awful about us all being different? If someone prioritizes accumulating wealth and has the ability to do, what is that to me? A “fair” tax system would have equality. Everyone paying exactly the same amount to fund out Government. Thank about it. If you go to the grocery store do they charge you differently depending on you 1040s? Now we all know that’s never going to happen. Those who have more are always going to pay more taxes. I’m fine with that. I’m not fine with the idea that the government has the right to regulate “Income Equality” or “Wealth Equality”. They regulate about everything else, and a line has to be drawn somewhere.

Excuse me?? Charging property taxes based on equity is ridiculous. That will induce people to have the highest mortgage possible to reduce taxes. People with money will just leverage there homes…. Duh!! In addition, if you reduce taxes for those with high mortgages it will increase affordability (ceteris paribus) and will actually increase home prices as more people bid for limited resources (homes)!!! You need to take a friggin econ class or two, then study the drivers of home prices before you write (or vomit) out a piece of populist swill like this!!!!!!!!

Don’t candy coat it… Tell us how you really feel! At any rate, when we try to tinker with things that don’t need tinkering we often get into trouble. I am all for creativity, but first you have to define the real problem you are trying to solve. Income inequality has been around forever, and isn’t going away, nor should it. Equal rights and being the same are two different things. I don’t see the problem clearly defined, let alone any sort of solution.