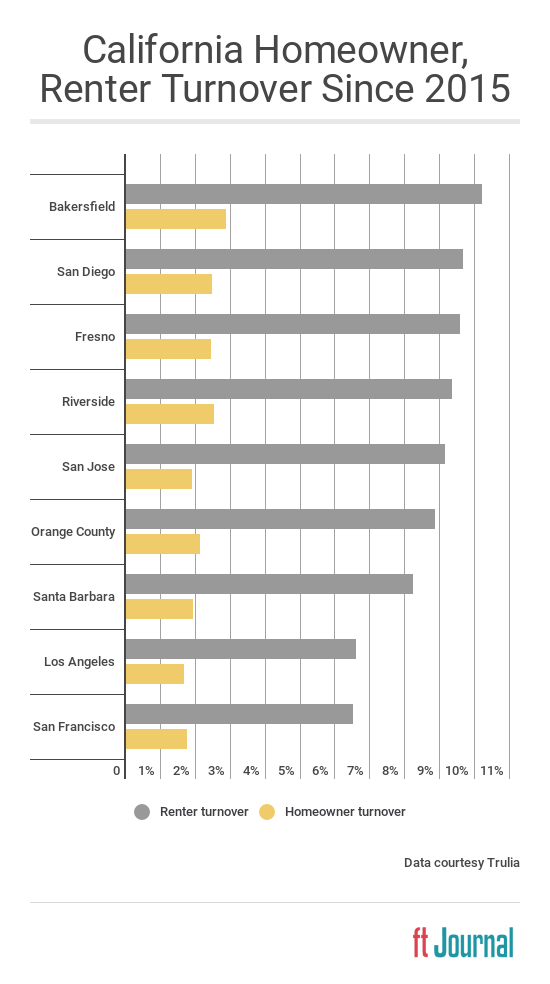

Good news real estate professionals: California is home to one of the most mobile populations in the U.S., according to Trulia.

Nationally, 2.27% of homeowners and 10.21% of renters have moved since 2015.

Here in California, renters actually move less often than the national average, while homeowners tend to move more often. But this all depends on what part of the state you live in.

The cities with the highest share of residents moving since 2015 are:

Astute readers will notice a trend emerge in the data presented above. Places where homeowners and renters move more often tend to be in the least expensive parts of the state.

For example, low-cost Bakersfield is the most mobile major city in California for both homeowners and renters. On the other hand, Los Angeles and San Francisco both see the smallest share of homeowners and renters moving in recent years.

This concept is called turnover, and it’s what drives the housing market.

Construction, low prices fuel turnover

Turnover — the number of residents who move each year — largely depends on the willingness and ability of homeowners and renters to move.

For instance, turnover is highest when jobs are abundant, wages are rising and consumer confidence in the economy is high. This is especially true for homeowners, who tend to “trade up” when relocating. Rising wages facilitate the ability to qualify for a more expensive home, while high confidence suggests promising economic conditions — and their paychecks — will continue.

In 2018, both factors are present, as buyers and renters are eager to cash in on California’s growing economy and their own increasing wages. But there is one thing holding them back — prices.

For evidence, consider the fact that turnover is lowest in areas of the state where home prices are highest. Home prices in these pricey metros have increased much faster than incomes. This turnover trend bucks the national tendency of turnover to be lowest in suburban and rural (less expensive) areas.

In Los Angeles, the median income rose 2.4% from 2015 to 2016, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. During the same time, average home prices increased 7% in Los Angeles, according to the Case-Shiller Home Price Index and rents rose 4%, according to Zillow.

When housing costs rise faster than incomes, residents who may otherwise wish to relocate are forced to stay put. This is especially true for households in rent-controlled units. Less turnover translates to fewer transactions (and fewer agent fees).

The solution to keep housing costs in line with income increases? More construction.

New residential construction in California is rising — very slowly. Unable to meet demand from the state’s growing population, new housing is falling short of what is needed to keep prices from bubbling over. The result is today’s low-inventory, high-priced housing market.

In the places where this dynamic is worst — California’s expensive coastal cities — turnover is lowest, and home sales volume is slowing.

The construction shortage will likely find a cure in the coming years, as new legislation designed to increase the housing stock takes effect. This, combined with the demographic push from retiring and relocating Baby Boomers and Millennials hitting the market as first-time homebuyers, will propel the market to the next golden age for housing, expected in the years following the next recession — sometime after 2021.