As the nationwide unemployment rate continues to soften, it’s time to take a step back, look at our economy and ask the important question: are we ready to stand on our own two feet yet?

The Federal Reserve (the Fed) continues to pump stimulus money into the economy by purchasing a mix of mortgage-backed securities and long-term Treasury securities. Further, it’s promised to keep short-term interest rates low at least until the nation’s unemployment rate drops below 6.5%.

The Fed’s aim is to keep rates low to stimulate business growth, creating more jobs for the many who remain unemployed. When more people are out of work (as has been the case since the 2008 recession), less consumer spending occurs. This tends to keep inflation at a minimum.

However, does the length of unemployment make a difference in spending, and thus prices?

This is the question a recent paper by Michael Kiley at the Fed addresses.

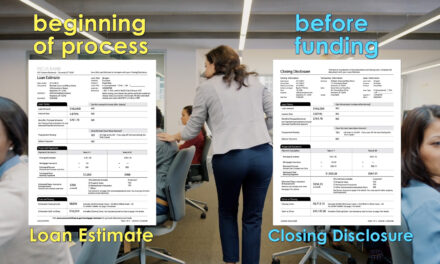

There are basically two types of unemployed individuals, in the eyes of economists:

- short-term unemployed (those jobless for less than 27 weeks); and

- long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more).

This chart from the Fed shows the percent of long-term unemployed spiking in the aftermath of the 2008 recession, remaining well above the short-term unemployment rate today:

The Fed economist finds that whether it’s long- or short-term unemployment, they both affect inflation the same way. That is, unemployment keeps consumer prices down no matter how long the average person has been jobless.

This is important because California’s unemployment rate, while steadily declining, has yet to return to normal. In fact, it hasn’t been this high since the early 1990s, as seen in this chart by first tuesday:

Editor’s note: In California, 38.5% of those unemployed have been without work for 27 weeks or longer as of April 2014, slightly higher than the national rate of 35.3%.

Now, returning to the original question: is our economy ready to stand on its own, without the help of federal stimulus?

It appears not. Now, before you point to what many have called a “recovered” housing market, reconsider the source of that recovery. Sure, home prices shot through the roof in 2013 and remain high today. However, prices have been propelled by cash-heavy investors, an unreliable (albeit mighty) force. Prices do not yet have the support of end users of property, the lifeblood of the housing market.

Those end users are still waiting on jobs. Many of them have been waiting for a very long time. Further, of those who have managed to secure employment, many remain underemployed. For example, 247,000 Californians (1.4% of the labor force) who usually work full time are currently working part time “involuntarily,” according to the California Employment Development Department.

The good news is California’s jobs recovery is almost back to pre-recession levels. However, with the intervening population increase of around 1% a year since 2008, jobs (and the unemployment rate) won’t likely catch up until 2017. Look to that year for a sustainable housing recovery in California.