Regulations for the use of land — zoning laws — are an inextricable piece of the fabric of our society. After all, without zoning our neighborhoods would become rife with crime and our business districts would be pure confusion. Zoning is necessary and our society is better for it.

Right?

No, not really. Zoning can’t create the perfect city, neatly separating spaces for living, retail, business and industrial activities — at least, not without significant consequences for its residents.

Here’s what zoning actually does in its present form across the U.S., particularly in California:

- Zoning restricts the amount of construction, especially residential construction.

- As a result, not enough new construction is built to accommodate demand for housing.

- Due to insufficient construction, the prices of new and resale homes rise considerably.

- Higher home prices reduce the quality of life for residents as less income is available to be spent in other economic sectors.

- An unstable housing market emerges, as home prices, while supported by a growing population relative to new construction, unable to be supported by an equal rise in income.

- Homeownership is stunted and home sales lag.

A brief history of zoning laws

Land use laws didn’t always exist in the U.S. In fact, the idea of officials telling a property owner how to use their land was seen as tyrannical, an overreach of the government. But this resistance to zoning gradually began to diminish at the start of the 20th century.

The first noticeable instance of zoning regulations in the U.S. occurred in New York City in 1916. Zoning was later allowed on a broad scale by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1926, allowing neighborhoods to restrict building types to single uses. Prior to this decision, it was unclear whether zoning hindered the rights of residents to use their private property as they saw fit. [Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. (1926) 272 U.S. 365]

But according to the Brookings Institution, zoning didn’t have any significant impact on local building trends until the 1970s. Until that point, construction mostly kept up with population growth, ensuring prices rose at a steady clip. Then, Baby Boomers started buying homes.

The largest generation to walk the earth (at the time), the Baby Boomers shaped our economy as we currently know it, including the housing industry. In fact, in many ways housing was unprepared for the convergence of Boomers on the market in the 1970s and 1980s. Demand for the American Dream propelled homeownership to the forefront of the Boomer imagination, and builders couldn’t keep up.

But builders weren’t held back due to a lack of lumber or workers or even enough land on which to build. Rather, land use regulations prevented builders from building in places where Boomers desired to live.

Undeniably, demand is highest for housing nearest to all the things that increase our quality of life, including:

- high-paying jobs;

- easy access to transportation;

- cultural amenities;

- high-quality schools; and

- superior infrastructure improvements.

But the proximity to these amenities needs to be balanced with the desire for space. That’s because zoning regulations hold down density, limiting the number of units built in desirable areas. Space became a high commodity in urban centers, with the high cost to show for it.

As the Baby Boomers looked to settle down, the only place with the right combination of space and location was the suburbs. Suburban sprawl became a regular feature of the U.S. landscape. Isolated bedroom communities spread like parts of an island chain connected by congested highways and long commutes.

Zoning in California

Here in California, the lack of appropriate zoning has led to historically low construction numbers.

For example, between 1981 and 2017 household growth exceeded new construction by 335,000 households. Thus, as demand from our state’s ever-growing population continues to rise each year, construction fails to keep up.

Put another way, California is home to 12% of the U.S. population, but only 10% of the nation’s housing stock. Again, this translates to hundreds of thousands of missing housing units from the state’s inventory.

As a direct result, California has the second-highest home sale prices in the nation in 2018, exceeded only by the District of Columbia, according to Trulia. For comparison, in 1960, California was home to the seventh-highest home prices in the nation, according to the U.S. Census.

Another result of low construction and high home prices is the state’s low homeownership rate. During 2017, California’s homeownership rate averaged a low 54.4%. The U.S. average homeownership rate was ten percentage points higher, at 64%.

But some progress is being made to reverse these past several decades of destructive zoning.

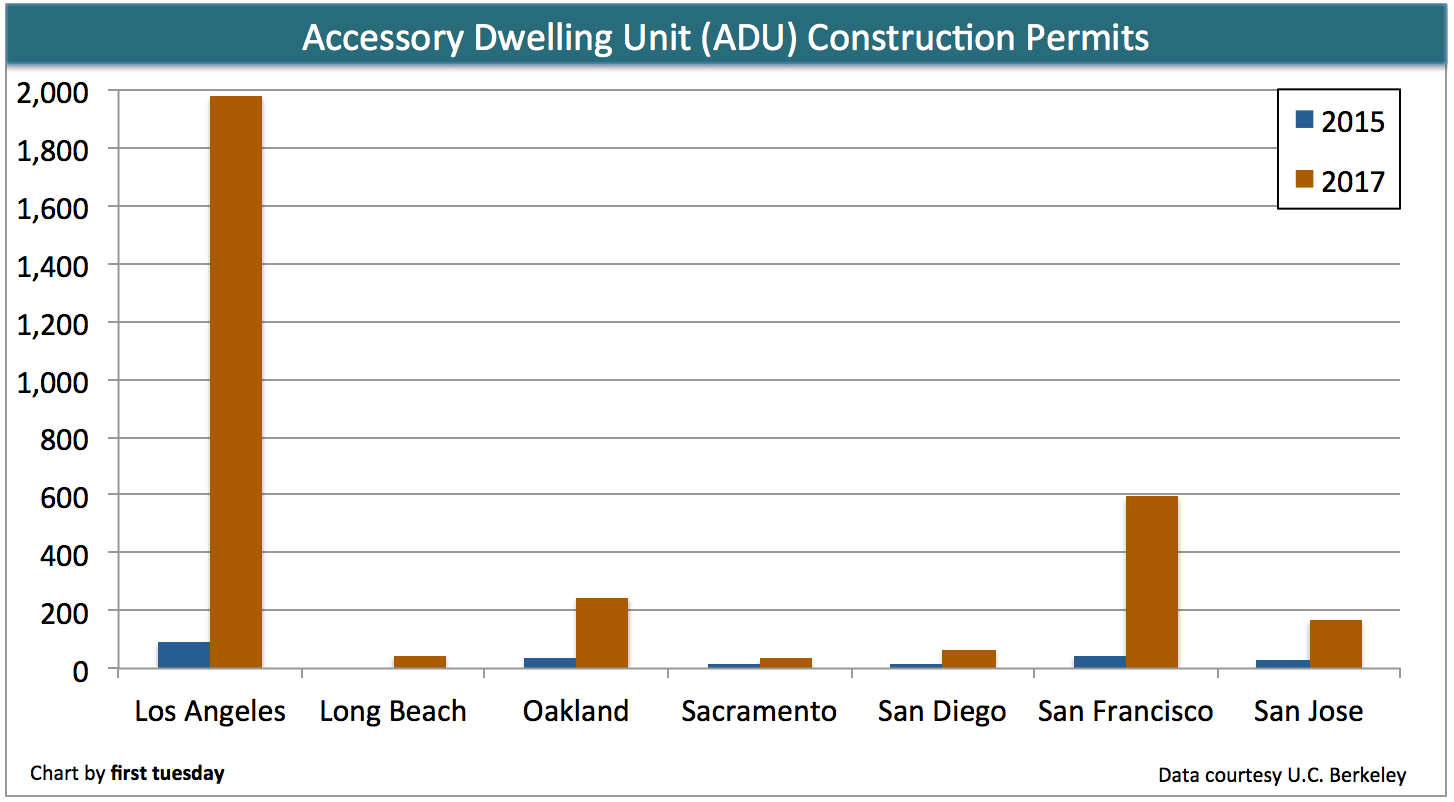

For example, new laws to encourage accessory dwelling units (ADUs) were enacted statewide in late-2016. The effect was immediate, as construction permits for ADUs jumped in 2017, from:

- 90 in 2015 to 1,980 in 2017 in Los Angeles;

- 0 in 2015 to 42 in 2017 in Long Beach;

- 33 in 2015 to 247 in 2017 in Oakland;

- 17 in 2015 to 34 in 2017 in Sacramento;

- 16 in 2015 to 64 in 2017 in San Diego;

- 41 in 2015 to 593 in 2017 San Francisco; and

- 28 in 2015 to 166 in 2017 in San Jose, according to University of California Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

Related article:

This jump in ADU creation was not due to any builder incentives or government-funded program. It cost taxpayers nothing except for the time paid to legislators who changed the law through their regular course of work. The jump was due entirely to progressive zoning changes.

Future zoning strides

California’s government is increasingly being made aware of the state’s housing crisis, and is reacting with new legislation designed to increase construction. Specifically, they are trying to find ways to increase the housing stock of units within reach of low- and moderate-income households.

In 2017, California passed a package of affordable housing bills. The changes in these bills included money to assist local governments in:

- reforming zoning codes to make housing production more efficient;

- reducing environmental analysis for affordable housing projects;

- streamlining the permitting process for affordable housing projects;

- constructing homeless shelters; and

- providing assistance to transition members of the homeless population.

Related article:

Real estate professionals need to know: new affordable housing laws

But local efforts to enact these changes are met by vocal not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) advocates. These individuals are interested in preserving their neighborhood’s “character” by limiting density and building height. NIMBYs are twisting the original aim of zoning for their own isolationist demands.

But the problem for local city council members who enact the state’s affordable housing agenda is this: NIMBYs tend to be the only ones who let their voices be heard. NIMBY advocates actually attend city council meetings to complain about proposed developments and changes. That’s because they have more of an apparent stake in any changes.

But real estate professionals have a stake, too. If more housing is not built to accommodate the state’s ever-growing population, prices will continue to rise out of reach. The first-time homebuyer population — the solid base of a healthy and growing housing market — will shrink. Today’s currently low home sales volume will continue for years.

This is why it’s imperative real estate professionals get involved in making sure NIMBYs are not the only ones heard. New housing development is needed to revive and sustain California’s housing market. Make sure it doesn’t get blocked by neighborhood residents who have not seen the full picture.

There’s lots of housing being built in the Santa Clara/West San Jose/Sunnyvale area, but almost all of it is rental, by large corporations such as Irvine Company and Prometheus, and renting for pretty much at “luxury” prices. This inventory doesn’t help the typical real-estate professional.

As far as long-time residents (or what the author refers to as NIMBYs), they actually make very good customers for the RE professional if you know how to meet their needs when they are ready to make that move, with residences in desirable areas that they’ve fervently “protected” from school overcrowding, high density next to single family home, conversion of open space, or the proposed liquor store nearby. Be sure to befriend them!

If realtors want more houses to sell quit voting for Democrats. Now they’re getting involved with creating more units which always means low income proposals which never work. How about cutting taxes and regulations that drive businesses out of California in droves? Texas says thank you for all the commerce and prosperity created for them with the help of insane Sacramento Democrats.

Mark S. needs to move to Texas; I recommend Houston.

Unfortunately, the author is totally inexperienced in knowing what it takes to obtain land-use entitlements. Also, unfortunately most developers lack what it takes, too, and seek to ramrod permits. I’ve successfully obtained land-use entitlements in 25 local jurisdictions in California. Streamlining the permit process is not the answer; better to streamline one’s attitude and beef up one’s knowledge of the entitlement process. BTW secondary units started long before the timeline noted in the article; again, lack of knowledge leads to disseminating bad information. To know the answer, many will have to look in the mirror and not the land-use codes.

I believe that your article on zoning is entirely wrong and one sided, the very thing you accuse NIMBYS of in the article. The current level of construction, has created horrible gridlock on streets and highways in California’s major cities. Construction and increased density without corresponding improvements in roads and public transit is a formula for disaster.

I live in the Santa Monica Mountains. We have narrow streets and minimal parking. We are a high fire severity zone. Additional “units” “granny flats” or whatever you want to call it is impossible, as there is no parking. More street parking will not allow emergency vehicles to get up the streets in an emergency. Homes in the Santa Monica Mountains are expensive and adding an “accessory unit” will not result in more affordable housing, just more density of expensive housing.

I purchased my home in an R1, single family neighborhood. If my zoning is to be changed, I should have some right to vote on whether I want that change. I did not buy my home and work to pay my mortgage for the last 30 years to now be told by some politician, or you, that I now must accept a zoning change to duplex.

I am sorry that everyone cannot afford to live in Beverly Hills or Bel Air. I did not inherit money, I worked for it. This is what we refer to as Capitalism. There is a lot of space to build in California without increasing density to the point where there is no quality of life for anyone.

What has held back reasonable construction of housing are the foolish and failed concepts of rent control. Most of the people I know who live in rent control buildings are well off. They are not being rented by the people who supposedly need them. There is no incentive for builders to build if they cannot make a profit. If they had a profit incentive again, they would build.

Please grow up and take a more reasonable approach to your article writing on this subject.