California’s average homeownership rate decreased slightly to 54.8% in 2019. This was down from the homeownership rate of 55.2% experienced in the prior year.

After trending down from its 60.7% peak in 2006 to its present level near 55%, the homeownership rate has finally stabilized at a normative level for the state.

California’s homeownership rate typically falls around 10 percentage points below the national average, partly due to the state’s more mobile population. Another culprit for California’s low homeownership rate is a lack of residential construction sufficient to support the state’s ever-growing population. This supply-and-demand imbalance forces homeownership out of reach for many would-be homebuyers, a dynamic which legislators are attempting to address in 2020.

However, as the next recession looms ever-closer in 2020, the homeownership gains California has experienced since 2016 are fragile. Whether our state’s homeownership rate remains near its historical level or declines alongside the global economy remains to be seen. It will depend on how low mortgage interest rates slide in the coming months and whether these low rates will be enough to induce homebuyers to return to a shaky market.

Post updated March 16, 2020. Original copy posted November 2013.

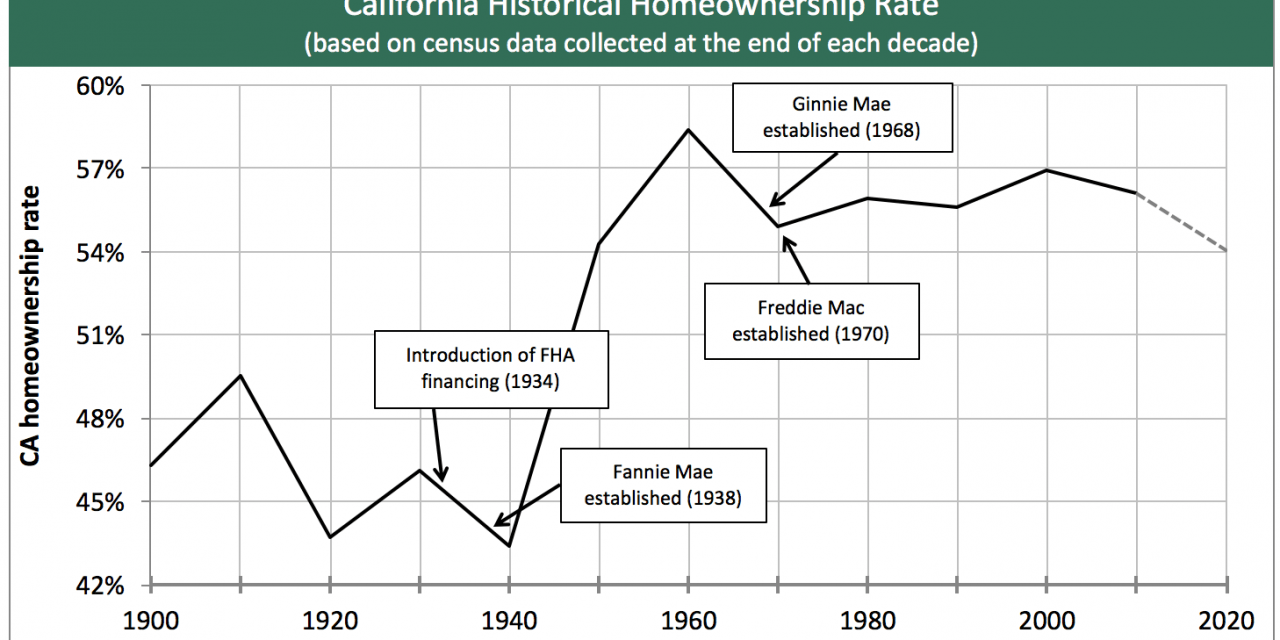

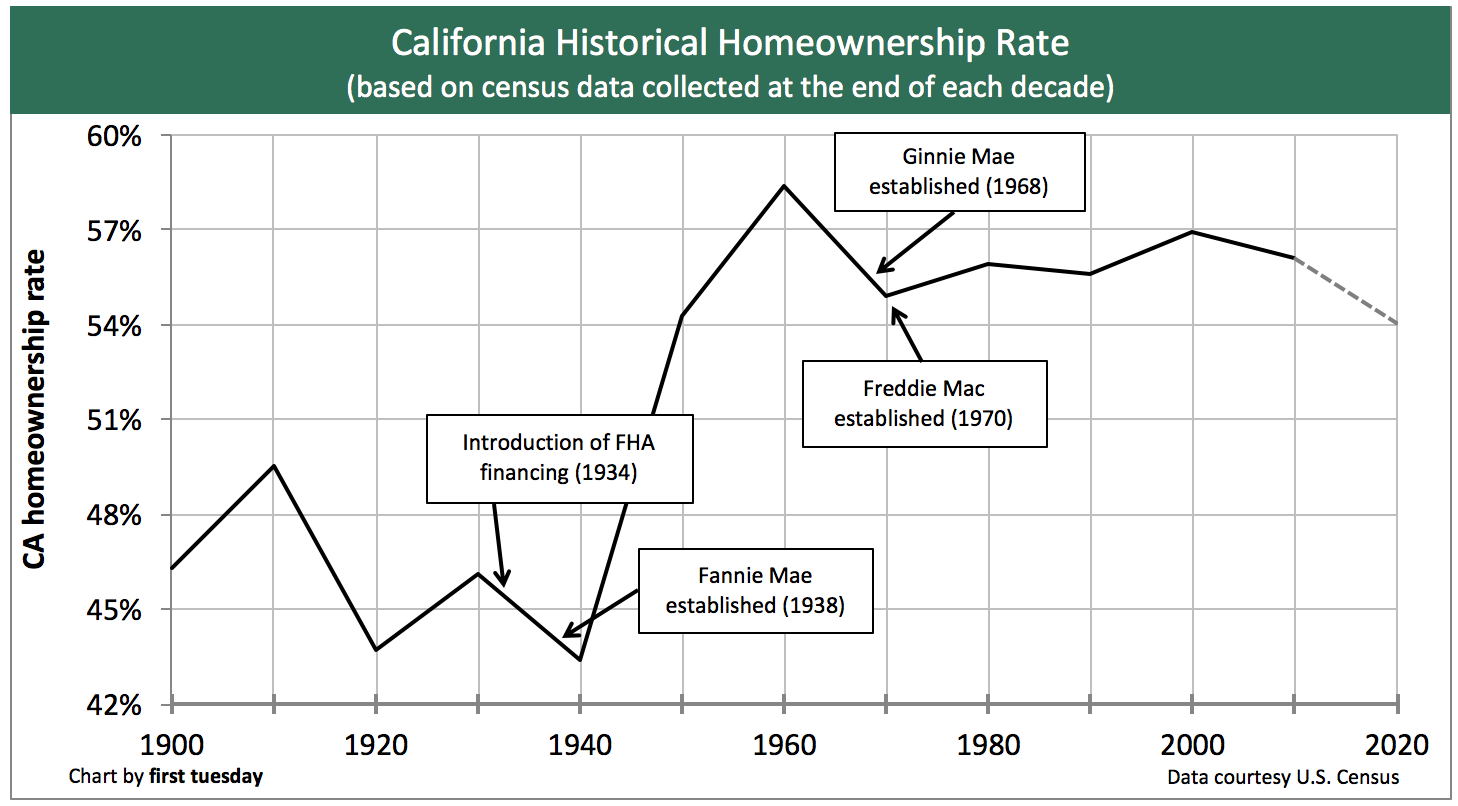

Chart 1

Reflects census data taken at the end of each decade

Chart updated 02/02/15

| 2010 | 2006 peak | 1940 low | |

| Homeownership Rate | 56.1% | 60.7% | 43.4% |

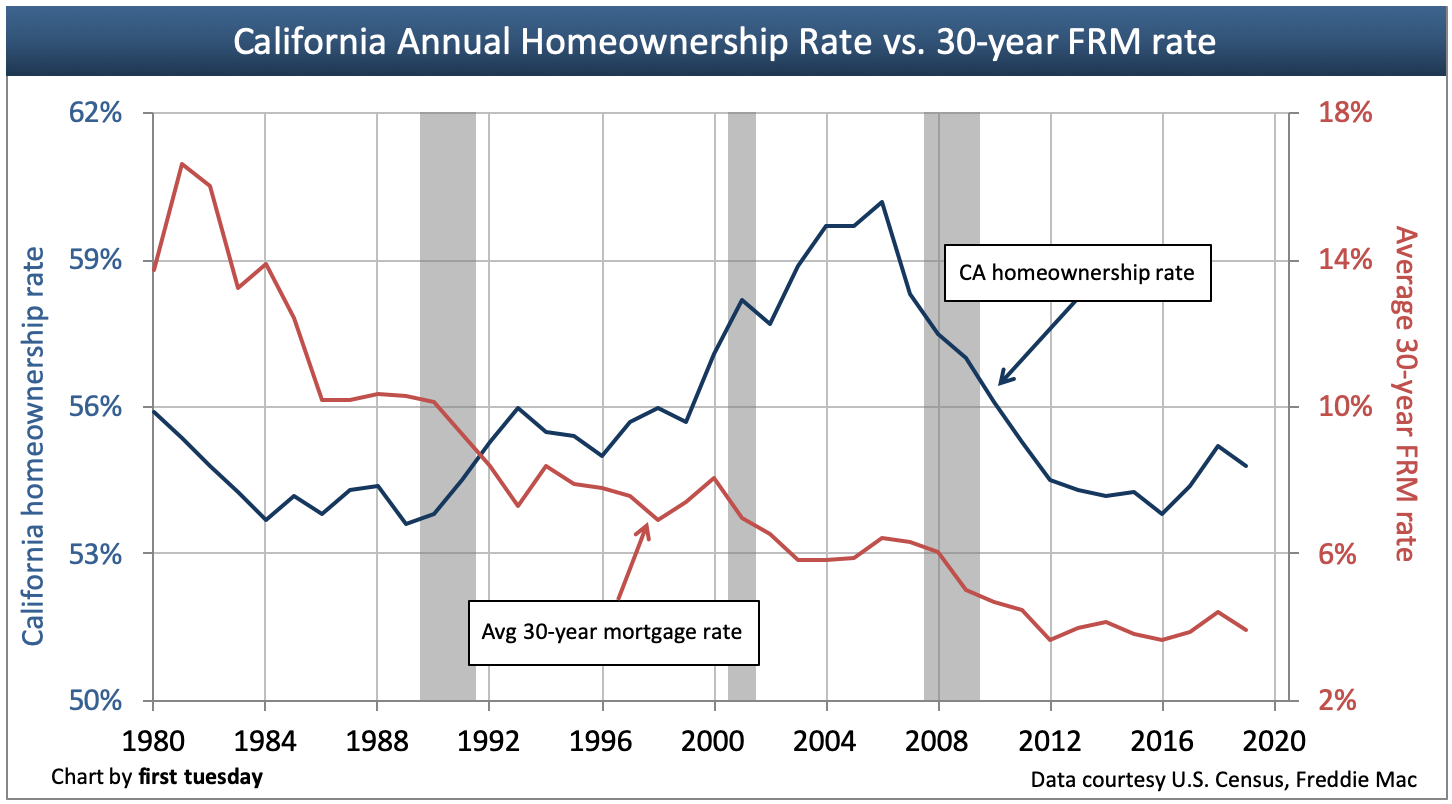

Chart 2

Chart updated 03/16/20

| 2019 | 2006 peak | 1989: 30-year low | |

| Average Homeownership Rate | 54.8% | 60.7% | 53.6% |

Past, present, future

California’s homeownership rate ballooned during the Millennium Boom, only to plunged with the great recession. California’s homeownership rate has finally stabilized around 55%, and what factors will contribute to future increases and decreases?

California’s homeownership rate is historically around 10 percentage points below the national homeownership rate (at 64.6% as of Q4 2019). This is due to a combination of factors, including the lesser impact the national policy of pushing the “American Dream” of homeownership has had on more mobile Californians.

California’s rate of homeownership has declined dramatically since the 2008 Great Recession, a drop of nearly seven percentage points since its peak year of 2006. But the Millennium Boom peak was an inflated figure, and 2019’s average homeownership rate of nearly 55% is closer to an historically appropriate level.

Understanding the factors which impact California’s low homeownership rate requires an analysis of several economic factors, demonstrated visually through the above charts.

Chart 1: The long view of homeownership

Looking at the century-long view of homeownership rates in Chart 1, you see the effects of related historical events. The most dramatic jump in homeownership followed World War II, between 1950 and 1960, when the percent of homeowners grew from 43% in 1940 to 58% 20 years later, a 33% build-up in homeownership.

While social events springing from the Great Depression and WWII had a strong effect on these numbers, the introduction of Federal Housing Administration (FHA)-insured financing in 1934 was a supporting influence, part of a developing push towards homeownership as a national housing policy. The FHA allowed virtually anyone with a steady income to finance the purchase of a home. Prior to FHA financing, only individuals wealthy enough to qualify with steep 50% down payments had the opportunity to own a home. Sellers frequently supplied the financing without which they could not sell.

Much later, Chart 1 shows the evolution of California’s homeownership rate as three factors are introduced:

- 1982: adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) make their debut in California (regulated variable interest rate mortgages (VIRs) had already been here for a decade);

- 1986: the federal right to borrow against your home equity as though it were an ATM under the Tax Reform Act of 1986; and

- 1997: the inception of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §121 principal residence profit exclusion.

The easy access to deceptively complex, enticing ARMs (which allow homebuyers to borrow more than they can with fixed-rate mortgages), along with the incentive provided by the principal residence profit exclusion and the Tax Reform Act of 1986, pushed the California homeownership rate beyond historical bounds of 55% to 60.7% in 2006.

This high rate of homeownership, quickly attained, proved unsustainable. Homeowners unqualified to handle ARMs once the rate and payments began to reset defaulted and returned to renting.

Related article:

Chart 2: Recent movements

In a non-recession market, homeownership rates drop as interest rates move upward to cool the economy, as reflected in the rate of homeownership during the late 1950s through the early 1980s. Chart 2 displays the generally unacknowledged converse relationship between the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage (FRM) rate and the homeownership rate (and home price trends) from early 1980 until 2006, at the beginning of the current Lesser Depression.

However, due to our Lesser Depression brought on by the financial crisis, after 2007 both FRM and homeownership rates have dropped in tandem. Today, the homeownership rate is still stabilizing, a correction of the effects of irresponsible lending during the Millennium Boom (not the fault of FHA or Frannie, but Wall Street bond market independence).

However, by mid-2016 the 30-year FRM rate will again begin to rise consistently, as it did in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and with that move, the homeownership rate will continue to lose strength before it fully stabilizes.

Looking forward

For the next 25 years or so, and in reverse of the direction taken during the past 30 years, interest rates will rise and this will inhibit homeownership – as occurred in the 1960-1980 period. The Fed intentionally raises short-term interest rates to deliberately induce a business recession when the economy is over-performing. The effects usually take hold in two to three years. More precisely, the recession sets in around 12 months after short-term rates rise above long-term rates.

This cyclical action has occurred periodically since WWII, until the early 2000s, when the Fed skipped the second phase of this action due to the events of September 11.

Related article:

Using the yield spread to forecast recessions and recoveries

Just as the recession’s magic was removing inefficiencies in the economy, fiscal and monetary moves post-9/11 led directly to the Millennium Boom. In the boom, as aided and abetted by financial deregulation, low-tier home prices were artificially driven to a three-fold high. A new real estate paradigm was prematurely declared in which prices would go up and up forever, in defiance of economic principles. Bond rating agencies, properly induced by Wall Street Bankers, fully endorsed the concept. Of course, this false paradigm came crashing down in 2007, and we have been in recession and recovery mode ever since.

The Fed finally increased interest rates in December 2015. However, fixed rate mortgages (FRMs) won’t rise for several more months. This is due to a number of complex global economic factors at work. Namely, economic chaos in much of the world has caused a lack of available “safe” investment opportunities. One investment opportunity deemed reasonably safe is the government’s 10-year Treasury (T-) Note. As long as many global markets remain unstable, foreign investors will continue to invest in the 10-year T-Note, keeping it and other rates tied to it – like FRM rates – low.

Apart from the effects of the interest rate cycle of rising and falling rates, the evolving societal mores of the younger generation show an increasing tendency towards renting, rather than owning, one’s shelter.

Related article:

Lenders vs. owners and the real estate interest of each : 2000-2011 and beyond

Looking forward on another plain, the homeownership rate will stabilize when California’s employment level reaches its 2007 pre-recession peak.

While jobs finally returned to the December 2007 peak in the second half of 2014, we have only just recently reached the percentage of California’s population employed in 2007, since we experienced a population increase of over 10% from 2007 through 2019 – just in time for the next recession to arrive in 2020.

Related article:

Finally, the high number of short sales, trustee’s sales and bankruptcies, while now past, will continue to have a lingering effect on the homeownership rate. The reduction of demand by removal of these displaced homeowners is the culprit.

Home ownership in California is not going down because this article does not discuss all the methods of home ownership. Home ownership among those who reside in California is going down. However, if you factor in foreign investment and people who buy homes in California who do not live in this state home ownership is up quite a bit. There are very few unclaimed or unowned properties or house in California. If you track sales of homes you will notice those have not declined. I don’t think this is a bubble because as long as foreign investment is coming in to buy homes and real estate the prices will continue to be held high.

13 -48 bp (unch frm 9:30)Dollar/Yen: 110.

Interest rates go down but home ownership goes down anyway?? Property values going up steeply over median income??? What does this tell you?

STOP!!

Bubble time