This article explains and formulates the liability of a breaching seller for any increase in the buyer’s loan rate due to a delay in closing.

An offset for interest rate changes

A buyer in escrow obtains a commitment for a purchase-assist loan, as called for in the purchase agreement.

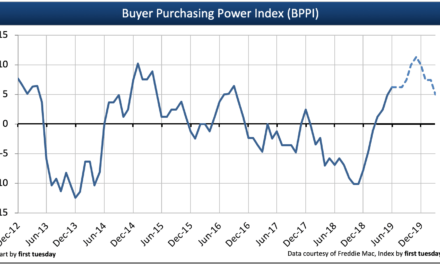

During the escrow period, real estate values surge upward, followed by an increase in interest rates.

Hoping to get a better price in the newly competitive market, the seller cancels his sale escrow instructions days before the scheduled closing.

The buyer makes a demand on the seller to perform under the purchase agreement and escrow instructions. The seller refuses and the buyer files a specific performance action.

The interest rate on the purchase-assist loan, a condition of the purchase, increases in the time lapse between:

· the date scheduled for performance (close of escrow) in the purchase agreement breached by the seller; and

· the specific performance judgment at trial in favor of the buyer.

May the buyer reduce the purchase price by an offset in the amount of the increased interest the buyer will pay for the purchase-assist loan now needed to close escrow?

Yes! It is foreseeable interest rates will rise when a seller breaches. Thus, it would be unreasonable for buyers to pay the original purchase price and any higher interest rates at the time of specific performance.

If increased rates on the purchase-assist financing were not borne by the breaching seller, the buyer would be prohibited from enforcing a purchase agreement by specific performance. [Hutton v. Gliksberg (1982) 128 CA3d 240]

If interest rates drop before specific performance is awarded to the buyer, the buyer is solely allowed to enjoy this benefit without a credit to the seller since:

· the seller cannot benefit from his misconduct which prevented the timely closing [Calif. Civil Code §3517]; and

· the buyer has incurred no loss.

Calculating interest losses

Two methods exist for calculating future money losses sustained by the buyer on an increase in interest rates:

· the loan-term formula, based on the dollar amount to be paid on the interest rate increase over the full term of the loan, discounted to its present value [Hutton,supra]; or

· the ownership-term formula, based on the dollar amount of the increase over the buyer’s anticipated holding period before refinance or resale, discounted to its present value. [Stratton v. Tejani (1982) 139 CA3d 204]

Loan-term formula

For example, monthly payments on a loan origination at an interest rate of 14% with a 30-year maturity on a principal of $400,000 would be $4,739.49. The same loan amortization at 9.25% carries a monthly payment of $3,290.70 which was available to the buyer at the time scheduled for closing.

The difference in the monthly payment resulting from the increase in the interest rate is $1,448.79 per month. Over 30 years, this difference will cost the buyer an additional $521,564.40 in actual out-of-pocket dollars.

Discounting this dollar amount at the current rate of 14% over a 30-year period results in a present cash value of $122,274. Thus, awarding the buyer $122,274 now indemnifies the buyer for the increase in the monthly payment caused by the seller’s breach.

The loan-term formula indemnifies the buyer for future losses over the entire life of the loan without considering the likelihood the buyer will refinance or resell before the loan term expires.

Ownership-term formula

The alternative method of accounting requires an approximation of how long the buyer intends to retain ownership of the property subject to the loan. Does the buyer intend to retain the property for a short-, medium- or long-term holding period?

The ownership period for which the seller is liable for the increased rate runs until the buyer anticipates he will resell or refinance the property. Thus, the buyer is not awarded a windfall if the interest rate drops and the buyer refinances or resells — a more equitable and economical approach than the loan-term formula.

To establish the probable ownership period before refinance or resale, consider:

· whether the property is residential or investment property;

· the buyer’s prior ownership history;

· ratio of the monthly payments to the buyer’s income; and

· the buyer’s employment.

These same ownership and economic arguments apply when a buyer is making financing decisions for the funding of purchases during a period of high interest rates on long-term mortgage financing in a weakened real estate market.