When the financial levies broke

In 1998 America’s central bank, the Federal Reserve (the Fed), started raising short-term interest rates to induce a routine business recession. As planned, the recession took hold in early 2001, one year after the Fed finally pushed short-term rates higher than long-term rates. However, the effort to cool the economy was short-lived as the economic reaction of both the Fed and the administration to September 11, 2001 froze the price of homes at their artificially elevated peak. [For a discussion of the yield spread, the difference between two key interest rates, see the December 2010 first tuesday article, Using the yield spread to forecast recessions and recoveries.]

Without real estate going through the normal downward market movement to return prices to their historical pricing trend, the stage could not be set for sustainable future real estate prices. Thus, owners of real estate, prodded by the policies of the government, were erroneously led to believe they had come under a new paradigm in real estate economics. This hazardous myth prophesied that the deregulated financial markets, which had evolved since 1980, would never allow real estate prices to fall below peak levels, but would merely stabilize them for a period until demand would again push prices upward. Simply, prices could only move upwards, and at worst, stay stagnant. Some economic pundits labeled this financial concept the “Greenspan Put,” in reference to a put option.

After September 11, the Fed, the U.S. Treasury and the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac opened the floodgates controlling the flow of money into mortgages. The Fed assisted by lending and buying treasuries in the money markets, adding large amounts of fresh cash to the supply of money available through bankers of all sorts, be they mortgage or Wall Street bankers. Thus, the seeds of the Millennium Boom took root. [For more commentary on the history, purpose and function of the Federal Reserve as the nation’s central bank, see the December 2009 first tuesday article, The lender of last resort: understanding the function and methods of the Federal Reserve.]

This cheap, short-term money provided upwards of $2 trillion dollars for lending on adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs), ZAP (Zero Ability to Pay) and RIPOFF (Reverse Interest and Principal for Optional Fast Foreclosure) loans at enticingly low teaser rates, all with the express government intent to induce tenants into homeownership.

With the availability of easy money, Wall Street bankers had the impetus to provide mortgage funds to as many borrowers as possible. As a result of this aggressive lending environment, lending parameters became lax and subprime borrowers were lured into homeownership through the use of exotic loans under the belief they would be able to quickly refinance to more favorable terms before the loan reset. This practice was consistent with the government’s ultimate goal of driving the percentage of homeownership in the U.S. from the stable and historical 64% figure of the prior 20 years to a destabilizing 70% of the population.

The potential disadvantages of homeownership for those seeking to relocate to new or transferred jobs to improve their labor skills, or cope with family dysfunctions such as divorce or disease, were never part of the dialogue. Tenants who turned into first-time homeowners purchased real estate without the requisite understanding that they no longer had the mobility to move freely about the country, prisoners inside the brick and mortar shelters they called their “homes.”

This flood of money was both in excess of the true needs of people paying for shelter (as either tenants or owners) and cheap for the bankers to borrow (from the Fed and depositors) or receive (by taking profits and deposits on the sale of bonds driven up in value due to Fed activity).

Releasing more than just money: mortgage market deregulation

During the same period, the U.S. Treasury and Congress (erroneously encouraged by the Fed) continued deregulating and removing the lending parameters restricting mortgage lenders and Wall Street bankers.

At the time, the tortured reasoning behind the extensive deregulation of mortgage lenders was that Wall Street would inherently look out for its own best interests. By this logic, as a matter of professional practice, mortgage lenders would not take excessive risks as it would destroy their business of making and bundling loans. This flawed rational behavioral theory of freshwater economics overlooked the force behind comparative advantage between competitors of equal footing – large Wall Street bankers. Comparative advantage is a force which drives Wall Street mortgage bankers to produce ever greater profits in the short term in a race to retain their private sector investors who would otherwise go to the competitor producing a greater profit. The Madoff ponzi scheme was a product of this competitive pressure.

Wall Street bankers became more actively involved in the mortgage business in 2002. In doing so, they willingly bought thousands of real estate loans at premium prices from mortgage bankers who originated them as rapidly as the Wall Street gang demanded. Wall Street then bundled these real estate loans into pools of mortgages, each pool being separately managed under pool servicing agreements (PSAs), a process called servicing. Participation in the pools was then sold to investors in the bond market to recover the funds advanced by Wall Street to buy the loans.

The bondholders eventually consisted of millions of small and large investors, individuals and institutional, domestic and foreign alike. However, no one bondholder held any one mortgage. Instead, all bondholders in a pool indirectly held a minute interest in all the mortgages, many of them subprime, held by the pool, called tranches. Tranches were created within a single pool of mortgages to entitle different classes of investors within the pool to different priority claims on the interest income and principal from the mortgages, similar to third and fourth trust deed holders who have junior priority claims to the value of real estate securing their loans. This created a chaotic management environment for trust deed servicing.

Also, during the rush to buy loans originated by mortgage bankers around the nation, Wall Street began buying up the mortgage bankers to get direct control over profits from both the loan origination and bundling/securitization phases.

This Wall Street modus operandi was perfected by late 2004 when the Fed belatedly started to cut off bankers’ easy access to the Fed’s unlimited pool of funds by continually increasing the interest rate, significantly reducing the flow of funds into mortgages.

However, it was short-term financing that had supported the initial Wall Street involvement in mortgages. By the time short-term rates began to rise, Wall Street was almost exclusively relying on investor funds flowing into the mortgage-backed bond market. Thus, Wall Street no longer looked to the Fed to replenish the mortgage coffers since mortgage-backed bonds provided the mortgage bankers and mortgage loan brokers with the flow of loans they needed to bundle and sell. However, these mortgage-backed bonds were a volatile financial Frankenstein, particularly when the securities were backed by subprime ARMs which posed a serious risk of default.

Mortgage fundamentals vs. the American Dream policy

Government homeownership policy was another and significant triggering factor which fed into the Millennium Boom. Going into 2000, the “American Dream” of homeownership was being aggressively pushed by state and federal governments onto tenants. The government promotion was so successful it drove homeownership rates among the national population from 64% in 2000 to 70% by 2006. This race into homeownership was financed by $2 trillion in additional guarantees and borrowings by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, both GSEs (and presently government-owned). The funds came primarily from the Fed’s massive expansion of the money supply through their money-market operations. [For commentary on Fannie and Freddie’s current tumultuous condition, see the August 2010 first tuesday article, Fannie and Freddie need more help, before disappearing.]

Real estate industry gatekeepers only stoked the fire with the mantra of “buy, buy, buy!” Real estate brokers and appraisers deliberately rejected the rational tone carried by historic valuation techniques of replacement cost approach (land, labor, and materials) and the income approach (present worth of future benefits of ownership). Even when the income approach was implemented, appraisers used a cap rate they divined from comparable sales prices, not investment fundamentals. Further, they deliberately failed to capitalize the net operating income of a project with a rate which included a return of capital, a long-term yield (as though the property were clear of liens), compensation for asset oversight, a reserve for replacement of structural components and a risk premium for adverse future changes in local demographics.

The call of the wild: scammers, fraudsters and speculators

In addition to the entrance of novice, first-time real estate investors indirectly packaged into real estate via real estate investment trusts (REITS) and mortgage-backed bonds, this environment opened the door to scammers, fraudsters, rent skimmers, adverse possessors and speculators directly owning real estate as hit-and-run types, called flippers. These flippers sensed a quick profit in an artificial fast-moving rise in sales volume and prices.

Flipping ownership for profit was fertile ground for speculators beginning in mid-2003, and ending abruptly in early 2006, roughly a three-year run. Without the ability to resell within six months to one year, speculators who acquired property had to convert to landlording until market prices recovered sufficiently to produce a return on their investment.

Real estate scammers engaged in rent skimming collected rents from tenants, but deliberately failed to make mortgage payments to the lender. Scammers also appeared under the guise of foreclosure consultants, sometimes cloaked in Department of Real Estate (DRE) advance-fee approvals, or as attorneys (acting as brokers without a brokers’ licenses), and short-sale loan discount facilitators. [For additional information on the DRE’s handing of California licensees guilty of fraud, see the December 2010 first tuesday article, Break the law, keep your license: real estate-related fraud and the DRE.]

Financial cause and effect: time to pay the piper

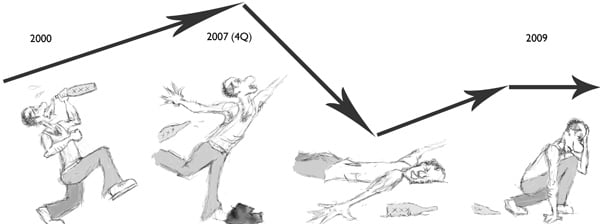

The Fed’s hyperactive lending through its open-market operations, coupled with the utter failure of regulatory agencies to perform and unsustainable government housing policy, caused the carnage of the real estate bust. Like a drunken New Year’s reveler, it was only a matter of time before the financial hangover set it. Thus, almost overnight, the cash-engorged hey-day of the Millennium Boom segued into the next economic epoch: the Great Recession.

Deregulation allowed mortgage lenders to take on ever riskier lending activity through 2007, the year mortgage borrowers began defaulting en masse and drowning mortgage lenders with foreclosures caused exclusively by imprudent lending practices. The Great Recession decimated trillions of dollars worth of asset wealth across the nation and left approximately 2,500,000 California homeowners (upwards of 30% of the state’s homeowners) in a negative equity condition, burying them in houses worth far less than the amount still owed on the mortgage. As a result, a majority of homeowners who bought during the Boom became prisoners in their own homes after the real estate bubble burst in December 2007, evaporating their home equity and preventing them from being able to sell and relocate.

To compound matters, as ARMs began to reset at higher rates, California homeowner who bought after 2001 didn’t have the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio necessary to obtain a loan refinance due to the lost equity in their property. California was thus faced with a foreclosure crisis of unprecedented proportions.

Congress was a willing accomplice, deregulating mortgage lenders and their Wall Street bankers by removing what few restraints remained on lending by 2005 after 25 years of loosening controls over mortgage lending. Without parameters within which lenders had to structure real estate loans, the forces of comparative advantage pushed Wall Street bankers to drastic leveraging to keep investors in their programs. This drove them to take on the excessive risk of loss built into ever more exotic loan terms, such as option ARMs.

Veterans of the real estate industry knew the result would be a disastrous collapse of both property values and public confidence in real estate ownership and mortgages. They will now have to wait until the bust morphs into a stable (more specifically, flat) volume of sales and prices that remains constant for a period of 12 to 18 months. Then they will be able to acquire real estate below or at replacement cost with a respectable rate of return at a 9-11% capitalization rate more suitable to income property investments – a return to basics once again.

In response to the vicious economic cycle of the imploding boom, the U.S. Treasury, the Fed and California’s state government released a wave of aid specifically targeting the real estate construction, sales and mortgage sectors. This aid took the form of:

- massive government subsidies (tax credits) to homebuyers; and

- Fed actions to keep mortgage interest rates unnaturally low by buying up large quantities of newly-issued mortgage-backed bonds (MBBs).

In California, $200 million from the state’s treasury by 2010 had been applied to the housing market on two occasions – subsidies totaling close to $400 million. The state’s 2010 subsidies granted $100 million in tax credits (prepaid taxes or refunds) toward the purchase of existing homes (primarily real estate owned [REO] properties) and another $100 million to the purchase of homes in builder inventory. [For a critical analysis of the tax credit, see the April 2010 first tuesday article, California’s homebuyer tax credit: an erroneous diversion of state funds.]

These stimulative actions taken by the state and federal governments temporarily propped up and gave the real estate market a bit of a sales volume and price boost in 2009 as intended. Thus, a majority of the improvements witnessed in the housing market were largely wrought by external “bridging” factors (government intervention), not organic industry growth. As first tuesday predicted in November of 2009, the economic recovery did not take the shape of the oft-cited” V,” “L,” “W” or “U” recessionary trends. Instead, it looks more like an aborted checkmark following the “dead cat” bounce during the period of mid-2008 to mid-2009 following the near total failure of real estate sales in January 2008. [For more information addressing the shape of the economic recovery, see the November 2009 first tuesday article, Divining the future: a letters game.]

We are now trudging over the long, choppy plateau of the aborted checkmark; growth in the coming two to three years will likely be quite modest, if not just plain flat. Though the Millennium Boom was devastating, the real estate market has begun to level out and will now experience slow but steady improvement going forward.

Looking forward

Though the volume of sales and leasing in the real estate market will be largely static in the near future through 2012 into 2013, reasons exist to be optimistic about the present – and the future. California agents and brokers – our licensed and entrusted gatekeepers – will not likely bank a fortune in the next two to three years, but many will be able to get positioned to acquire great wealth by the end of this decade. In these lean times of hugely reduced real estate sales activity with properties moving at half their 2005 prices, most agents who remain active full-time will only, for the moment, generate an income sufficient to support their minimal subsistence, nothing more.

Editor’s note – A collective decline of roughly 75% in personal income for California’s real estate licensees handling sales since the Boom years of 2004-2005 comes as a devastating financial blow to most.

The quantity of jobs in California directly impacts homeownership statewide. Without a paycheck, a family cannot pay rent for an apartment, or make mortgage payments on a house, unless they are subsidized by the government or possess substantial independent wealth. The basis for an individual’s creditworthiness, essential if they are to borrow money for housing, is the paycheck, self-employed earnings from a trade or business, or income from investments.

Historically, periods of reduced employment have lasted between four and five years — this time it will be longer, around eight years after the December 2007 peak. We predict slow but gradual job growth through 2012, picking up to 400,000+ annually through 2016 when we will have recovered all the 1,500,000 jobs lost after 2007. [For more information regarding unemployment, see the November 2010 first tuesday Market Chart, Reeling from California unemployment.]

California home prices will not fully stabilize until 2014, then prices will increase into a peak around 2018 as Generation Y matures into a vast demographic of first-time homebuyers. The return to the peak prices of January 2006 will not happen again until around 2025 – believe it and implement your investment plans around it, as any lost cash (and equity) in current property values is an unrecoverable “sunk cost.” [For more information regarding price peak predictions, see the October 2010 first tuesday article, Another prediction that California metro area price peaks won’t return until 2025.]

We at first tuesday look to the coming Generation Y demographic as an influx of new homeowners who will help clear out the inventory of vacancies and pull us out of this real estate quagmire. Until the price bump in 2018, Californians must be patient and agents must focus on preparing themselves to serve the new demographic of homebuyers in a more prudent spending climate anchored in market fundamentals. Investment in income-producing real estate to hold as a collectible for years to come needs to be the current search, but the time to actually buy at the best prices and on seller carryback terms is yet to come. [For more information regarding the future buying power of Generation Y, see the October 2010 first tuesday article, The demographics forging California’s real estate market: a study of forthcoming trends and opportunities.]

Actually, (contrary to Mr. Marix’s comment) this historical recitation is EXACTLY what is needed to understand the events that have transpired to date! Mr. Wallmark has succulently capsulated the many “fixes” drilled in to the American economy. The key point here is that many Americans have abdicated responsibility for their own state of health to “Big Government”. They simply expect the government to take care of us, fix us, and take care of our financial security. Furthermore Americans aren’t taught economics and business principles in school, and if they were you can bet it wouldn’t be Austrian Economics.

In Mr. Wallmark’s forward view, clearly the American public must see by now the closing in of the ranks. The wagons are circling and the only ones on the inside are the direct government workers and the bankers – leaving working stiffs on the outside.

That may be true, however the purpose of history is to help us avoid repeating the same mistakes. So like in a classroom, we need to hear it over and over so as not to blunder again. Plus Mr. Wallmark explains it exactly how and why it happened.

This historical recitation is of zero value.