In 2017, the Republican Tax Plan made numerous changes to how everyone reports, deducts and pays taxes for income earned in 2018. As this year’s tax season comes to a peak, homeowners are finally starting to feel the 2018 changes.

Changes to itemized, standard deductions

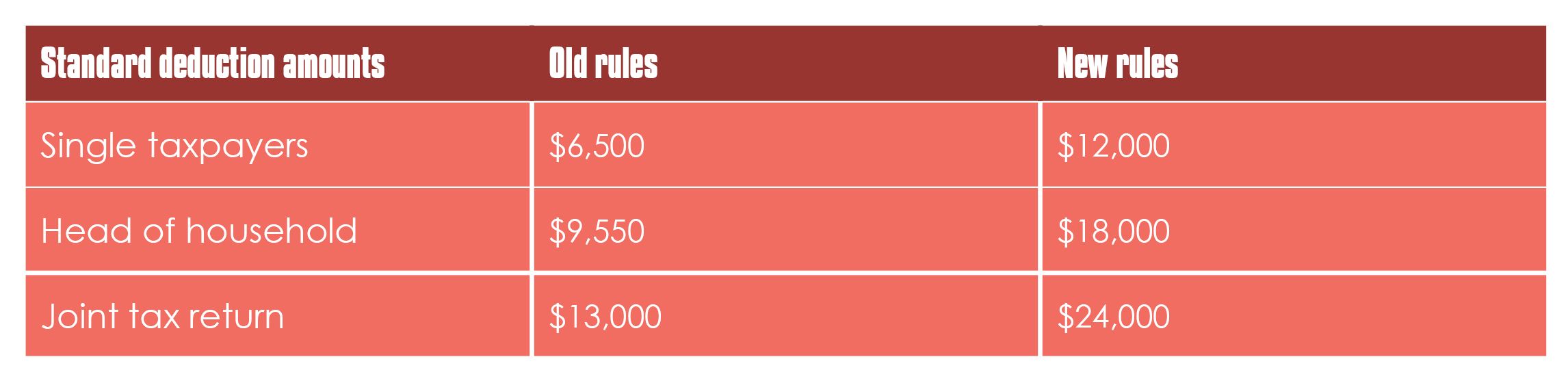

The standard deduction that U.S. households take roughly doubled from 2017 to 2018 — good news for low-income renters, but mostly bad news for homeowners and individuals with high personal income, specifically:

- households that annually take the standard deduction will see a tax liability reduction since the deduction from taxation is now much higher; and

- most individual Californians will now take the standard deduction rather than itemize, resulting in higher taxes for about half the individuals who itemized, generating a higher deduction under prior rules. [See Figure 2]

For homeowners, the mortgage interest deduction (MID) can only be taken if a homeowner itemizes their taxes. However, due to the higher standard deduction, fewer homeowners will need to take the MID in 2019 as to itemize will not produce a larger deduction.

For those who have itemized their deductions — and will continue to itemize under the new plan — some significant changes include:

- state and local (SALT) taxes are now limited to $10,000 per tax return (the same for single and joint filers);

- the ceiling for the MID has lowered from interest on mortgages of up to $1.1 million to interest paid on $750,000 — and interest on home equity loans and home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) only qualify for the MID when they funded home improvements; and

- the deduction for moving expenses is eliminated for all except for military families.

These changes have already had a significant impact in states like California where SALT taxes and mortgage amounts are both higher than average. The state’s high cost of living translates to higher tax amounts for residents. But under the old tax rules, SALT taxes used to be fully deductible. Now, they will only be deductible up to $10,000. For reference, the average Californian pays $18,438 in SALT taxes as of 2015. This means typical taxpayers in the state will now be paying taxes on at least an additional $8,438 in income.

California’s average SALT bill is the third-highest in the U.S. This is due to the state’s income tax rate and property taxes needed to fund services demanded of state agencies. Adding the $10,000 cap increases the average Californian’s federal tax payment by about $4,000 over their prior full SALT deduction.

CPI set to shift your income bracket

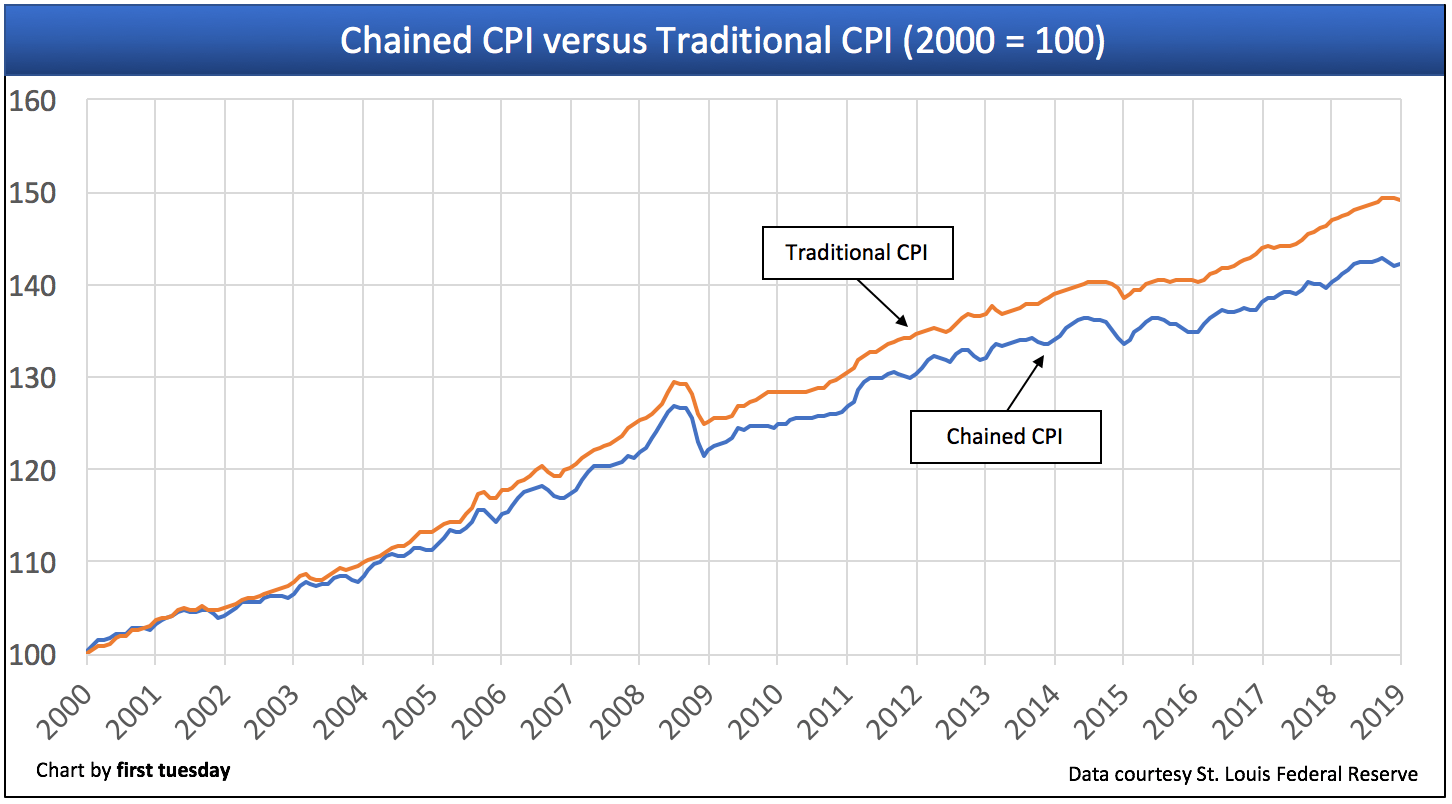

Income brackets have changed, as they do from year-to-year. But more importantly, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) will now measure inflation differently when making annual adjustments to the dollar amounts of brackets in the coming years. This essentially equals an insidious tax increase from year to year, as peoples’ future income taxes will increase more quickly than the consumer price index (CPI) measure and thus wages.

The new CPI measure to be used is chained CPI. The difference between the new measure and the way inflation was previously measured is the new measure accounts for consumer substitution patterns. Consider the example used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which publishes the chained CPI figure: when the price of beef rises, the traditional form of CPI uses this higher price of beef to increase the CPI measure directly. But the chained CPI figure accounts for consumers who might actually substitute another meat which hasn’t experienced a price increase, say, pork.

The overall effect is for chained CPI to rise more slowly than the traditional CPI measure. In turn, tax brackets will also rise more slowly. This means, when household income rises in the future, people will be shifted into higher tax brackets more quickly than under the old measure when inflation elevated these brackets more in line with rises in personal incomes. [See Figure 1]

Taxpayers will suffer what is termed bracket creep, when they move up into a higher tax bracket despite no real increase in income (after deducting for inflation). True, their income may have increased from the previous year, but not enough to actually up their purchasing power since consumer inflation exceeded their income increase.

The Tax Policy Center estimates the new CPI measure alone will equal an additional $125 billion in tax revenue by the year 2027, paid mostly by middle-income earners. This increase will be small at first, but will add up to more money paid each year by taxpayers as they are bumped into higher tax brackets.

Figure 1

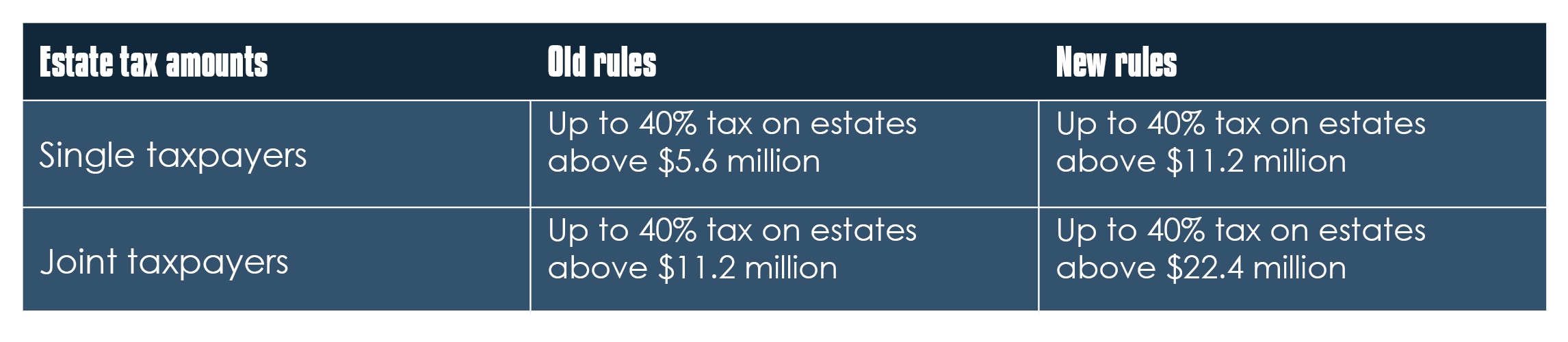

Estate tax changes

Very few individuals pay estate tax each year, and under the 2018 changes, this group has shrunk further.

The estate tax is a legacy tax on gifts (inheritance) left to family members or other individuals upon a person’s death. These taxable items include:

- real estate;

- cash;

- personal property;

- business assets; and

- insurance money.

However, the IRS normally taxes very few estates when individuals receive items upon a person’s death. This is simply because most individuals don’t exceed the threshold or lifetime exclusion for being taxed on their wealth at the time of death, as it was quite high under the old rules and is even higher under the new rules.

For example, under the new rules a single filing jointly won’t pay any taxes on inherited estates unless the estate exceeds $11.2 million. Thus, this “tax cut” impacts an extremely limited number of taxpayers. [See Figure 2]

Figure 2

Individual mandate removed

Taxpayers who don’t carry health insurance will no longer pay a penalty for remaining uninsured — this was called the individual mandate to induce everyone to be insured no matter the level of personal health.

The impact of repealing the individual mandate will be twofold:

- an immediate tax break for those taxpayers who did not have health insurance as they will no longer pay a tax penalty; and

- higher insurance rates for everyone who has health insurance.

The reason? The individual mandate was an effort to induce more healthy people to sign up for health insurance. These additional premiums helped insurers keep their costs down, and if not, the government collected a tax penalty to cover the increased cost of government payments to health insurers.

But now that healthy people don’t face a penalty for enrolling in basic health insurance plans, insurers are left with a higher share of sick people on insurance since healthy individuals will opt out. When more of the insured are using their health plans because of illness or other ailments, insurance become more costly.

However, the 3.8% tax on net investment income and profits added by the Affordable Care Act remains in place under the new rules. The Affordable Care Act added a 3.8% tax on net investment income and profits (classified as unearned income) when modified adjustable gross income (AGI) exceeds a threshold of $250,000 for joint filers (or $200,000 for single filers). For real estate investors, this includes income and profit from:

- the operations and sale of rental property; and

- interest income on savings and trust deed notes, earnings on land held for profit and rents received on triple net leased property.

Other miscellaneous changes impacting real estate

Beginning in 2018 and through 2026, taxpayers may choose to defer the gain from the sale or exchange of property when the money is reinvested in a qualified opportunity zone within 180 days of the sale. [26 United States Code §1400Z-2(a)]

This rule rewards investors who put money into low-income areas which don’t often see investment, designated opportunity zones by California’s state government. Much like a §1031 exchange, the profit does not “disappear” in the eyes of the IRS. Rather, it is deferred until the investor sells the property or until December 31, 2026, whichever comes sooner. [26 USC §1400Z-2(b)]

Another change ushered in during the 2018 tax year is a decrease to the corporate tax rate for C corporations (a corporation taxed separately from its owners as distinguished from S corporations, partnerships and LLCs). Many brokerage firms are structured as C corporations and thus the decrease applies to them. Previously, the corporate tax rate for C corporations was graduated, capping out at 35%. Now, the corporate tax rate is a flat 21%. [26 USC §11(b)]

This tax reduction not only hugely decreases the amount of money C corporations owe the IRS, but it effectively increases the value of C corporation ownership – the investors holding the company stock.

The 2018 changes also include a cap to net operating loss (NOL) taken by a business. Previously, NOLs were able to offset up to the full amount of taxable income carried backward up to two years and forward by 20 years. Now, NOLs may only be carried forward, not backward, and the threshold is limited to 80% of the taxable income each year. [26 USC §172(a); (b)]

Tax changes impact home values

Before the 2018 tax changes, taxpayers who itemized their deductions were able to deduct the full amount paid in SALT taxes each year, essentially avoided the compounding of paying federal taxes on their state tax payments.

Now, SALT deductions are capped at $10,000 — the same for single and married taxpayers. For many Californians (and other taxpayers located in high-tax and high-income states, like New York and New Jersey), their SALT taxes well exceed the new cap. This translates to being taxed at the federal level on additional taxable income that under previous rules was deductible in full.

When it comes to housing, taxpayers with the most expensive homes — and thus higher property tax payments — are also paying more federal taxes under the new SALT limit. Higher tax payments by wealthier individuals will have a domino effect on home sales in California, causing reduced home values in high-tier residential properties, according to a study by the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank.

The CFRB study finds the average home value change across the U.S. will be -5.7%. In other words, home values will be 5.7% lower than they otherwise would have been under the old rules which allowed taxpayers to deduct their full SALT payments.

However, due to the state’s higher home values, this reduction will be much more significant for California’s homeowners. Here, the average price difference due to the SALT cap will be:

- -8.7% in Vallejo;

- -8.6% in Oakland;

- -8.6% in Riverside;

- -8.5% in San Diego;

- -8.4% in Los Angeles;

- -8.4% in Bakersfield;

- -7.7% in San Jose;

- -7.1% in Stockton;

- -7.0% in Fresno; and

- -5.9% in San Francisco.

This negative price change will be on top of any other market factors – recoveries, recessions, immigration, trade – which push and pull on prices. For example, 2018’s rising interest rates and falling sales volume have already begun to pull back on home prices in 2019.

Related article:

I know of two native Californian families that are leaving the State just this month, to Washington and Texas. I know of more that have plans to move in the future. Expect an exodus of middle class families from this high tax State.

Simply, this means that real estate values in the mid-market will not be in great demand, resulting in lower values because people and businesses will move out of state. How can this trend be reversed? State and local governments must manage their budgets more responsibly and efficiently to soften the tax burden of homeowners and businesses, lessening the exodus from the state.

But will they? I doubt it.