Delayed disclosures trigger fraud and consumer protection contingencies

Many real estate practitioners erroneously believe in the in-escrow timeline set by trade union purchase agreements for first delivering seller disclosures and completing buyer inspections — including those set by the California Association of Real Estate (CAR)®. However, this is not the standard, and does not comply with the public policy set by California’s legislature and enforced by the California Department of Real Estate (DRE).

Provisions 14a and 14b of CAR®’s purchase agreement arbitrarily set time periods of 7 and 17 days after contracting for the delayed delivery of reports and disclosures covering the condition of the property and its location, and the buyer’s response.

Further, CAR®’s purchase agreement does not provide for compliance with public policy when making the disclosures before the buyer goes under contract — the moment of agreement on the price and property conditions based on the up-front disclosure of material facts.

The primary legislative intent prescribed by real estate law is to deliver property disclosures in a timely fashion — which is always before the seller’s acceptance.

When the seller or their agent delay disclosures beyond acceptance, provisions 14a and 14b satisfy the statutorily mandated additional remedy available to the buyer — the contingency.

When the buyer is not handed disclosures of property conditions prior to contracting, the statutory contingency is automatically triggered to help prevent consumer fraud. The contingency gives the buyer the additional right to cancel the purchase agreement, one of many remedies a buyer has against the seller and the seller’s agent arising from a delayed, in-escrow disclosure.

Disclosures of facts reveal real value

All property-related disclosures need to be delivered to the buyer as soon as practicable — meaning as soon as possible after commencement of negotiations and before entering into a binding contract. [Calif. Civil Code §§2079 et seq.; Calif. Attorney General Opinion 01-406 (August 24, 2001)]

As a matter of professional practice, buyers receive all property disclosures from the seller or the seller’s agent prior to determining a property’s value for submitting an offer to purchase.

When a buyer does not receive disclosures before contracting, there is an unlawful asymmetry of information about the property. This situation places the seller in a position of full knowledge and the buyer with only what they may have gleaned from a walk-through of the property.

Material facts — property information adversely affecting value — contained in property disclosures always factor into any prudent buyer’s pricing of a property. Thus, when the buyer is not in a position to review and consider the contents of property disclosures mandated to be delivered by the seller prior to contracting with the buyer, the buyer is essentially submitting a “blind offer” — entirely ignorant of the actual condition of the property. Here, there is no transparency of facts based on the aid of pertinent information known or readily available to the seller or the seller’s agent.

Disclosures reveal the precise condition of the property, and hence, its value. Only when the seller’s broker waits to provide disclosures after the buyer enters into a binding contract does the contingency provision in CAR®’s form for delayed disclosures kick in — as required by statute.

This asymmetry of information between the seller and the buyer of a deliberately delayed disclosure isn’t just bad for the buyer — it’s bad for the seller and the seller’s broker.

By statute, the delay triggers a contingency whether or not included as a provision in the purchase agreement form. Worse, the activity provides grounds for claims of misrepresentation of property conditions and deceit occurring the moment the seller goes under contract to sell.

When the seller delivers the transfer disclosure statement (TDS) to the buyer after the seller enters into a purchase agreement, the buyer may:

- cancel the purchase agreement on discovery of undisclosed defects known to the seller or the seller’s agent and unknown and unobserved by the buyer or the buyer’s agent prior to acceptance [CC §1102.3];

- make a demand on the seller to correct the defects or reduce the price accordingly before escrow closes [See RPI Form 150 §11.2]; or

- close escrow and make a demand on the seller for the costs to cure the defects. [Jue v. Smiser (1994) 23 CA4th 312]

Buyer’s right to cancel on delayed disclosure

Delivery of the seller’s TDS to the buyer is deemed to have occurred in a timely fashion when the TDS is attached to the purchase agreement offer made by the buyer or the counteroffer made by the seller. [CC §1102.3; see RPI Form 304]

When the TDS is belatedly delivered to the buyer — after the buyer and seller enter into a purchase agreement — the buyer may, among other monetary remedies, elect to cancel the purchase agreement under a statutory three-day-right to cancel. The buyer’s statutory cancellation right runs for three days following the day the TDS is actually handed to the buyer (five days if delivered by mail). [CC §1102.3]

However, as many sellers’ agents have discovered, buyers on their in-escrow receipt of an unacceptable TDS or home inspection report (HIR) are not limited to cancelling the purchase agreement. Monetary remedies and equitable ownership laws are available to them based on failure of upfront disclosures by in-escrow disclosures.

Demand to cure a material defect undisclosed when contracting

As an alternative remedy, the buyer may make a demand on the seller to cure any undisclosed material defect affecting value which was known or should have been known to the seller or the seller’s agent prior to the seller entering into the purchase agreement.

When the seller’s agent knew or is charged with knowledge of the undisclosed defects at the time the buyer and seller entered into the purchase agreement, the buyer’s demand to cure the material defect may also be made on the seller’s agent. [See RPI Form 269]

When the seller does not voluntarily cure the defects on demand, the buyer may close escrow and later recover the cost incurred (or lost value) to correct the defect.

The buyer is not limited in their recourse by the purchase agreement contingency provision referencing only the statutory right to cancel the transaction for the seller’s failure to timely disclose. Defects known and undisclosed or inaccurately disclosed by the seller or the seller’s agent at the time the seller accepts the buyer’s purchase offer impose liability on those who knew or are charged with knowledge.

Sellers’ agents have a duty to know what they are marketing and then disclose what they have observed or determined about the property’s conditions. [Jue, supra]

Price reduction in lieu of cancellation

Another alternative to cancelling is for the buyer to tender an amount for the price reduced by the cost to repair or replace the defects known to the seller or the seller’s agent and untimely disclosed or first discovered by the buyer while under contract. [See RPI Form 150 §11.2]

When the buyer makes a demand on the seller to correct the defects undisclosed at the time the acceptance occurred, they hand an HIR to the seller or the seller’s agent together with a buyer’s request for repairs form. Thus, the buyer may waive their right to cancel and rely on the deficient disclosures existing at the time of contracting. [See RPI Form 269]

The buyer’s request for repairs is essentially a checklist, typically based on property defects set forth in an in-escrow receipt of an HIR report.

The request for repairs calls for the seller to repair, replace or correct the defects unknown to the buyer at the time of acceptance, and do so prior to closing the transaction and delivering possession to the buyer — an effective alternative buyer remedy.

The “as-is” fallacy

Agents continue to perpetuate the misconception that incorporating an “as-is” clause in the purchase agreement means they can market and sell the property in its present undisclosed condition. For many agents, “as is” is synonymous with “no further disclosure required.”

The words “as is” do not mean “no disclosure required” by the seller, regardless of the type of real estate transaction or sophistication of the buyer. Since disclosures are mandated, “as-is” treatment has been specifically called out and outlawed.

“As-is” provisions are disruptive of proper conduct to disclose the condition of the property in a timely fashion. As mandated, the seller simply needs to disclose the defects, whether or not they agree to make repairs.

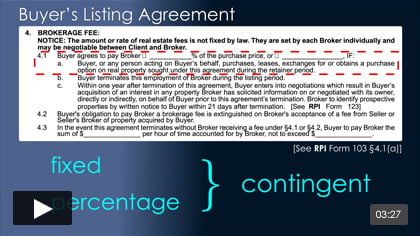

Related video:

Further, “as is” implies a failure to disclose something adverse known to the seller or their agent, a prohibited activity. In contrast, “as disclosed” is the condition of the property as known by the buyer when the seller accepts their purchase agreement offer. [CC §1102.1(a)]

Thus, all buyers purchase property:

- “as disclosed” by the seller, the seller’s broker and the broker’s agents; and

- “as actually observed” by the buyer prior to entering into the purchase agreement.

Include a home inspection

A competent seller’s agent will aggressively recommend the seller retain a home inspector to perform a home inspection

The HIR is used in the preparation of the seller’s TDS to make disclosures. Using the HIR for TDS disclosures bars claims for defects against the seller and the seller’s agent. Both are presented to prospective buyers before the seller accepts an offer, to provide maximum risk mitigation of claims made by the buyer on the seller and the seller’s agent.

Related article:

This article was originally posted September 2016, and has been updated.