The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) is cutting annual mortgage insurance premiums (MIPs) down by 0.5 percentage points for the following mortgage values:

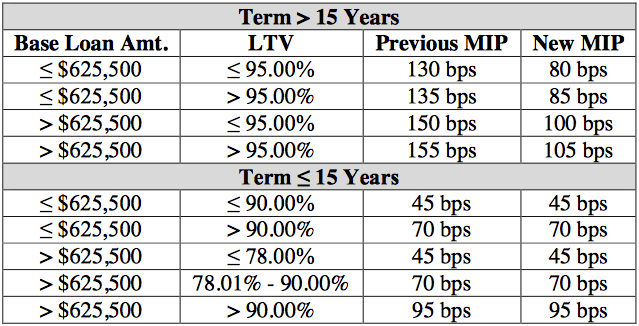

Table courtesy U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). See Mortgagee Letter 15-01.

Table courtesy U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). See Mortgagee Letter 15-01.

The new rates are effective for mortgages with case numbers assigned on or after January 26, 2015. The new rates do not apply to single family forward-streamline refinance transactions for existing FHA mortgages that were endorsed on or prior to May 31, 2009.

A press release by the Obama administration claims this reduction will save new FHA homebuyers an average of $900 a year in annual MIP, and that this will surely attract more potential homebuyers who otherwise may feel priced out. What was not said is that the rate being reduced actually produces the premiums needed to cover anticipated losses in FHA mortgage insurance programs. Reduced premiums means a higher risk of the Treasury needing to subsidize losses again.

Still, it all sounds like good news for consumers. But, two caveats prevent us from getting out the champagne just yet.

First, an annual MIP of 0.85% is still higher than the average private mortgage insurance (PMI) rate, which is 0.79% on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage (FRM) as of December 2014. So, why even bother with FHA mortgages when homebuyers can get the same low down payment option with cheaper PMI?

Second, the FHA’s encouragement for lenders to engage in risky mortgage lending is irresponsible. We just brushed the economy off from the last housing crash, so why artificially push the housing market toward that ledge once more?

The FHA’s minimum down payment requirement is 3.5% (slightly higher than Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s new 3% minimum). This makes it easier for low-income earners to enter homeownership. However, with home price changes often fluctuating above 3.5% a year, the potential for losing home equity and thus defaulting is high.

Yes, making homeownership more available to lower- and middle-class households is a valuable goal for housing policy makers. However, a better way to do it is to increase the housing supply in desirable areas, specifically through changing zoning laws to better suit housing demands and keep prices from exceeding replacement costs.