How often do your real estate clients inquire about earthquake safety or insurance before buying?

- Seldom. (71%, 17 Votes)

- Some of the time. (17%, 4 Votes)

- Most of the time. (13%, 3 Votes)

Total Voters: 24

This article is the final installment of a three-part series on the effect of natural disasters on California’s real estate market. For part I of the series, see: Drought. For part II of the series, see: Sea level rise.

Earthquakes: Yesterday and tomorrow

“People need to know that the shaking is not over. We’re going to get hit again and it’s going to be a bigger monster. The earth will literally crack open.”

These words are uttered by Paul Giamatti’s character as he explains to a reporter the coming earthquake in the 2015 summer blockbuster, San Andreas, which is about — you guessed it — California’s San Andreas Fault. The movie goes on to demonstrate in vivid detail the horrors that await cities near the fault line like Los Angeles and San Francisco — even Bakersfield doesn’t get off scot-free.

While the movie was a bit of an exaggeration, it played off real fears moviegoers have about experiencing the “big one.” And in California, these fears aren’t entirely unfounded.

There have been 54 major earthquakes in California since 1900, defined as an earthquake of at least magnitude 6.5, and/or causing loss of life or property damage greater than $200,000, according to the California Geological Survey. The last major earthquake was a magnitude 6.5 and occurred on December 22, 2003 in San Simeon, causing substantial damage in nearby Paso Robles.

With 54 major earthquakes over the past 115+ years, one major earthquake occurs on average every 2.1 years. Therefore, it appears California is well overdue for a major earthquake.

Where will the next big earthquake occur?

Statistically, the next “big one” (of around magnitude 8.0) will occur along the southern end of the San Andreas Fault, according to geologist Pat Abbott of San Diego State University.

Most of California’s populated areas are located in or near an earthquake hazard zone. The exception is California’s Central Valley, encompassing cities like Fresno and Sacramento (property lying east of I-5 north of Delano and south of Redding). Here, you are as safe as you can be (in California) from earthquakes.

The West Coast of the United States is particularly susceptible to earthquakes, as it lies alongside the western edge of the North American Plate, where it butts up against the Pacific Plate. Students of Geology may recall the Ring of Fire, which encircles much of the Pacific Ocean. California makes up a significant portion of the ring, though its main symptom is earthquakes, rather than the volcanoes experienced in much of the Pacific.

You can read more about the San Andreas Fault at the U.S. Geological Survey.

The ground shakes

When an earthquake occurs, one fault slides against, underneath or on top of another. This direction can be vertical, horizontal or somewhere in between. There are several different types of faults (and you can view a nice animation by the U.S. Geological Survey, here).

The San Andreas Fault is a transform fault, meaning it does not subsume land to another fault, nor is it subsumed. Rather, the two plates — the North American and Pacific Plate — move past each other, in a horizontal fashion. When this occurs, observers on the ground may not notice the evidence the fault movement leaves behind, but from the air it is clearly visible:

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Can scientists predict earthquakes?

The ability to predict earthquakes does exist, but the warning time is short and California has yet to fully implement an alert system.

It works like this: There are two types of waves that occur when an earthquake strikes. The shear waves or “S” waves cause the shaking that is so destructive to property. However, several seconds before the “S” wave hits, a mostly silent primary wave, or “P” wave, arrives. Dogs and other animals sensitive to sound can detect P waves, but human ears usually cannot. Earthquake predicting technologies alert the user when a “P” wave is detected. This gives the user a few seconds to head for cover, turn off a gas stove, exit an elevator or complete any last-second preparations. The warning time depends on how deep the quake is and how far the epicenter is from the user.

California is in the test phase of the ShakeAlert System to provide advance warning of imminent earthquakes. Japan already has a similar system in place, which provides nationwide alerts of a coming earthquake. It has been credited with saving thousands of lives during Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Mexico City also uses a similar system.

Individual homeowners can purchase earthquake predicting technology for their home, though as it is still an emerging technology here in California, success is not guaranteed.

After the ground shakes

In addition to the initial shaking of the ground and potential damage to buildings and property, earthquakes cause a lot of indirect damage as well. Earthquakes can cause:

- ground failure, which refers to landslides and liquefaction (when loose, wet or sandy soil shifts during the shaking and causes building foundations to sink or move);

- tsunamis, large waves caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or underwater landslides; and

- dam failure, which results in localized flooding.

Therefore, even if a property is not located near a fault, it may be located in an area where an earthquake may indirectly damage it. These areas are identified in geologic maps, available at local city planning departments. Dam failure inundation maps can be found at the Office of Emergency Services.

Disclosing earthquake fault zones and other hazards

An earthquake fault zone is an area of land where portions of the Earth’s crust meet. For example, the San Andreas Fault extends over 800 miles from northern to southern California. Property located within a certain distance of this fault, as designated by the State Geologist, are in an earthquake fault zone. [Calif. Public Resources Code §2622]

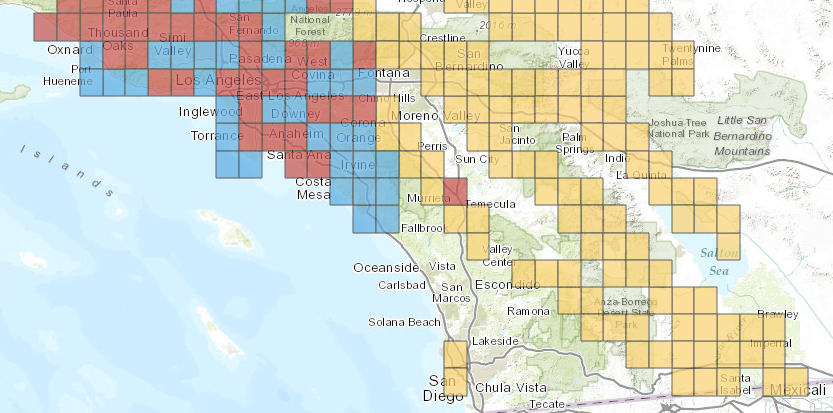

Image courtesy California Geological Survey

The map above shows a broad picture of earthquake fault zones — the yellow and red boxes — in Southern California (the blue boxes are landslide and liquefaction zones and the red boxes are both earthquake and landslide zones). There are 105 cities in California that contain earthquake hazard zones (view the list here). However, just because a city is listed doesn’t mean that the entire city is in an earthquake hazard zone. To find out if a specific property is located in an earthquake hazard zone or any other hazard zone, view maps at the property’s local planning department.

Editor’s note — Hazard maps provided by local planning departments don’t always provide a clear picture of the actual threat from fault lines. However, earthquake and seismic hazard zones are required to be disclosed in the Natural Hazard Disclosure (NHD) Statement, regardless of the accuracy of the local hazard map. If fault data is unavailable, the NHD allows the seller to mark “not yet mapped.” [See RPI Form 314; 315]

Information about seismic hazard zones can be found at the California Geological Survey.

Property located within an earthquake fault zone is subject to natural hazards. Other natural hazards include property subject to:

- special flood hazard areas, which also become a concern to homeowners following an earthquake;

- potential flooding and inundation areas;

- very high fire hazard zones;

- wildland fire areas; and

- seismic hazard zones (where soil displacement may occur due to seismic activity, even though it is not located on a fault). [Calif. Civil Code 1103(c)]

Whether a seller lists the property with a broker or markets the property themselves, the seller is to disclose to prospective buyers any natural hazards known to the seller, including those contained in the public record.

To unify and streamline the disclosure by a seller (and in turn the seller’s agent), the California legislature created a statutory form called the Natural Hazard Disclosure (NHD) Statement. [See RPI Form 314]

The NHD Statement is required on all types of property. [CC §1103.1(b)]

Compliance by the seller and the seller’s agent to deliver the NHD Statement to the buyer is required to be documented by a provision in the purchase agreement. [CC §1103.3{b); See RPI Form 150 §11.5]

If the residential or commercial seller provides a Homeowner’s or Commercial Earthquake Safety Guide to the buyer, there is no further duty by the seller or their agent to provide additional earthquake advice. [CC §2079.8; 2079.9]

Other required actions

As a further precaution, all residential water heaters are required to be anchored, braced or strapped to prevent movement during an earthquake. Further, a residential sellers needs to state whether the home’s water heater is anchored, braced or strapped. [Calif. Health & Safety Code §1921(a); (b)]

If the seller’s water heat does not comply, the seller is advised to include a written statement on the transfer disclosure statement (TDS) disclosing that fact. [See RPI Form 304]

Los Angeles recently passed legislation requiring roughly 15,000 buildings be retrofitted against future earthquakes. Landlords of apartment buildings will have until 2024 to complete retrofitting. Landlords of commercial buildings will have until 2042 to complete necessary retrofits. The cost will be shouldered by the owners of the properties, and likely to be passed along to tenants.

Insurance against disaster

Normal homeowners insurance does not cover earthquake damage. However, earthquake insurance exists to provide coverage to homeowners in the event of a tremor. But does it pay off?

Earthquake insurance is rarely worth it. Following the Northridge Earthquake of 1994, when insurance companies had to pay out unexpectedly enormous sums to cover their clients, premiums and deductibles rose and paybacks decreased. Now, a homeowner has to really get “lucky” (read: your home has to be totally destroyed) for the amount of premiums paid to pay off. Even then, homeowner deductibles are higher than most saving’s accounts. Therefore, it may end up being a total loss anyway.

A better investment is to take the money you may spend on earthquake insurance premiums and use it to pay for retrofitting, if the home is not built to withstand a large quake. This includes:

- bolting the home to its foundation (this costs a few thousand dollars depending on the state of the home’s foundation);

- bracing or reinforcing walls for older homes or those that were built improperly (another few thousand dollars); and

- homeowner fixes like strapping heavy appliances, furniture and televisions to walls (hundreds of dollars at most but usually less).

Homeowners are encouraged to hire an experienced retrofitting company to inspect the property and provide estimates for the work to be completed. Easy fixes like bolting furniture and moving heavy objects from top shelves to bottom shelves ought to be done as soon as practical, and by homeowners in both outdated and brand new homes.

Even with the extra cost to retrofit or insure homes against earthquake damage, California’s home values are hardly suffering from earthquake fears. Some of the most expensive real estate around is located practically on top of California’s most active fault lines — in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

That being said, if a homeowner chooses to retrofit their home, when they eventually sell they need to include that information in their home’s marketing package. Buyers will appreciate the fact that they won’t have to worry about making these improvements and it may even make them aware of other properties that haven’t been retrofitted, making the retrofitted home stand out.

Share more earthquake tips with your clients — download and personalize the free FARM letter: Earthquake safety tips.

To read part I of this series, see: Drought. To read part II of the series, see: Sea level rise.