Richmond, California’s plan to retake their housing market is bold. We take you past the misinformation to the facts.

What the plan entails

Facts

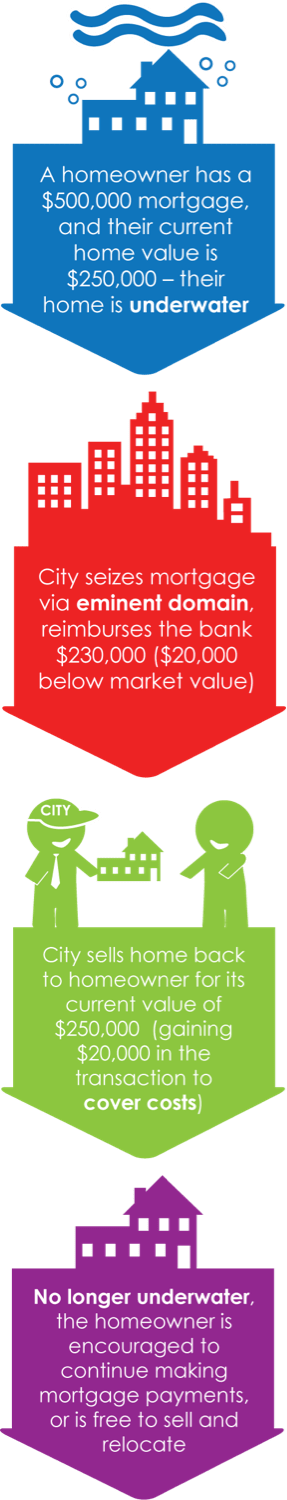

Richmond’s plan is to seize severely underwater mortgages through the power of eminent domain (called reverse eminent domain by some). Seized mortgages are reduced in line with each property’s current fair market value (FMV), determined by comparable sales.

Richmond plans to start seizing mortgages within the “next several months,” according to city mayor Gayle McGlaughlin. The hope is other California cities will join in the plan, forming a Joint Powers Authority, which will then seize the mortgages.

Winners in this situation include the homeowners involved, and Richmond’s broader economy.

The losers in Richmond’s plan are the lenders who will no longer be able to cash in on the higher mortgage payments required under Richmond’s toxic, underwater mortgages. Further, in each reverse eminent domain transaction, Richmond will reimburse lenders for less than market value in order to cover the risk of default (and costs). For example:

Editor’s note: Participation in the program is voluntary for homeowners, but compulsory for lenders. Richmond officials have threatened that if lenders refuse to participate, the city has the option to seize the actual homes.

Fiction

Is this even legal?

A lawsuit brought by big banks (including Wells Fargo) against Richmond alleging reverse eminent domain is unlawful was recently dismissed. The lenders claimed the city’s eminent domain plan violates constitutional protections for private contracts. If Richmond successfully seizes mortgages under reverse eminent domain, these lenders (and several more) have threatened to withdraw from the area or increase mortgage rates on Richmond-area borrowers.

Is that legal? The answer is no. These threats sound a lot like redlining, targeting buyers for less advantageous loan terms according to their geographic region.

Lender histrionics aside, the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, known as the public use clause, outlines the groundwork for Richmond’s reverse eminent domain process.

“No person shall be… deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

Two well-cited cases support this reverse eminent domain plan and fall under the public use clause. The first, Louisville Joint Stock Land Bank v. Radford, states reverse eminent domain is acceptable and permissible, so long as the mortgage lenders are justly compensated and public interest requires it. [Louisville Joint Stock Land Bank v. Radford (1935) 295 US 555]

In the second case, Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff, the Hawaii legislature enacted the Land Reform Act of 1967, stating the Hawaii Housing Authority (HHA) has the ability to condemn private land for public use. Once the land is purchased by the HHA, the HHA sells the land back to the lessees to become landowners. [Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff (1984) 467 US 229]

The main factors involved in both of these cases (being for the public good and just compensation for the mortgage lender) are followed in Richmond’s reverse eminent domain plan. The one potential hang up may be with the city’s plan to reimburse the banks at slightly below market value to cover costs.

Big paydays for the undeserving?

Fiction

Some will tell you this reverse eminent domain program is benefitting Richmond’s partner in the plan, Mortgage Resolution Partners (MRP), first and homeowners last. However, MRP is not paid by the community it helps. Nor does the fee MRP receives depend on the price the community pays for the acquired mortgages. MRP is paid the same flat fee per mortgage that a lender earns through a mortgage modified under the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP).

Facts

MRP is the company who put the reverse eminent domain plan together for Richmond. It’s a self-identified community advisory firm working to stabilize local housing markets and economies by keeping underwater homeowners in their homes.

Richmond’s eminent domain program is called Community Action to Restore Equity and Stability (CARES). CARES is privately funded and completely voluntary. Homeowners who choose not to refinance are not affected. The mortgages are chosen by the local governments and the local governments decide which mortgage acquisitions and which areas make the most difference in their communities.

CARES targets mortgages trapped in private securitization trusts (essentially, mortgages that were bundled and sold on the private market to investors, making it difficult for them to qualify for loan modification programs). Incentives are created for homeowners to maintain good credit to qualify for the program. The plan is designed and controlled by each local government who chooses the mortgages and methods to meet local needs. Each local government has the ability to include other types of mortgages, such as delinquent or defaulted ones.

Underwater homes aren’t a big deal anymore

Fiction

Home prices rose across California in 2013, hurtling most underwater homes out of negative equity. So why doesn’t Richmond just drop their eminent domain plan — it won’t even help many homeowners, will it?

Facts

It’s true, negative equity has diminished in California, with just under 13% of mortgages underwater as of Q4 2013. However, the figure is much higher in areas the recession hit hardest, according to a report by U.C. Berkeley. In Richmond, 28% of homes are still underwater and prices remain at half the peak home prices experienced during the Millennium Boom.

Thus, nearly one in three mortgaged homes are underwater in Richmond, and they are unlikely to see daylight until the next big bubble. These homeowners need help now — not in some distant future.

The current plan is to use eminent domain to restore equity on 624 homes. However, taking this action will open the door to extensions of this plan in the future, both here in Richmond and across the nation.

It’s immoral!

Fiction

The loudest vitriol against the campaign to help homeowners comes from Wall Street, specifically big banks and mortgage companies who made a tidy profit shelling out these mortgages in the first place. Are they concerned when it comes to the mounting number of underwater homeowners?

The sad truth is investors stand to profit from the continuing foreclosure crisis. Private investor firms like Colony Capital and Pimco (a vocal opponent of using eminent domain to seize mortgages) are deeply invested in buying these foreclosed homes on the cheap and converting them to rentals.

On the other side of the same coin, there is no money in helping underwater homeowners stay in their homes.

The “immorality” clearly doesn’t stem from Richmond’s eminent domain plan.

Facts

If anything, this plan should have been enacted earlier, and on a broader scale. The New York Fed has called reverse eminent domain “the best way to assist underwater homeowners.” President Obama considered the plan in 2008, but backed down in the face of opposition from those aforementioned Wall Street types.

Don’t let vocal opponents sway you, too. Lenders are not out in the world to help borrowers stay in their homes — they are out for money.

The detractors of Richmond’s reverse eminent domain plan want you to blame the borrower, but excuse Wall Street for preying on these homeowners. It’s the same type of logic that goes into arguments against strategic default – and we’ve debunked those, time and again.

I agree completely with this analysis. Big business has never had a problem with eminent domain that displaces homeowners when it is done to build freeways and ease congestion or to create access for developments. At best, it would seem that intermediate scrutiny (used in equal protection challenges to gender classifications, as well as in some First Amendment cases) is applicable under the constitution to this process. An argument can be made that only a rational basis applies (generally used when in cases where no fundamental rights or suspect classifications are at issue). If rationally related, the statute must be rationally related to a legitimate government interest, no question property degradation due to being over encumbered would pass the rationally related test because almost everything does. If the higher test of intermediate scrutiny applies, Richmond’s plan seems to further an important government interest by means that are substantially related to that interest.

In the end, this ends up more of a political question than a legal one, which the courts are never going to touch.