In the third presidential debate, Donald Trump mentioned U.S. economic growth was below 1% in 2016, worse than the economies of China or India (both developing nations and thus prone to faster growth), which are growing at 6% and 8% respectively. He blamed today’s slow growth on the weaker manufacturing industry in the U.S. and suggests the nation is being held back by bad international trade deals.

Another theory offered by Hillary Clinton was that today’s slow growth is a carry-over from the 2008 economic recession. Clinton proposes government investments in the middle class, while Trump claims the solution is in the upper class by extending more tax cuts to those at the top of the income spectrum.

How do the candidates’ theories apply in California?

A recent Vox article examines the various potential causes for the continued sluggish national economy. It observes a decline in gross domestic product (GDP) growth following each recent economic recovery. For instance, annual GDP growth averaged:

- 5% in 1982-1989;

- 2% in 1991-1998;

- 8% in 2001-2007; and

- 1% in 2009-2016.

It’s true, economic growth has slowed across the U.S. considerably in recent years. But this is not the case in California.

GDP: not a national matter

California, the world’s sixth-largest economy, experienced GDP growth of over 4% in 2015, according to the California Department of Finance. This was the highest year-over-year GDP increase since the year 2000.

California’s GDP is going strong because our state is fueled by robust industries — namely relating to science and technology. Further, foreign-owned businesses have large investments in California, employing hundreds of thousands of workers in the state. Tourism is another booming industry, drawing domestic and international visitors (and their dollars) to the state’s parks, cities and beaches.

You might expect home sales to have played a significant role in California’s recent GDP growth, since home values have spent the last four years climbing through the roof. However, most home sales are excluded from GDP measures, to avoid counting a home resale more than once. Only new construction is included.

But that doesn’t mean that much of California’s wealth isn’t concentrated in the housing market. In fact, our state’s real estate industry accounts for approximately 17% of all economic activity in California, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The downside to our booming GDP and housing industry is that these wealth gains are concentrated at the top of the economic ladder:

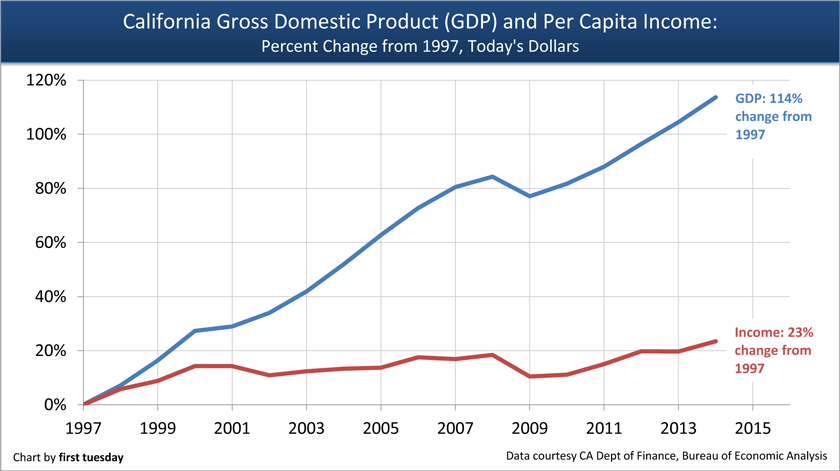

While GDP has grown steadily over the past two decades, average income has barely increased. Profiting most from GDP increases are the wealthiest class of individuals — the large business owners and those whose primary earnings come from passively earning income through investments (members of the rentier class). Members of the high-income class are also the biggest beneficiaries when home values rise, since these individuals already own property, sometimes multiple properties.

Those who suffer when home values rise rapidly include low- and moderate-income renters, and those who wish to become first-time homebuyers but are unable to keep up with home prices, which rise faster than their incomes can keep up.

Therefore, while California doesn’t have the same problem of slow economic growth as the rest of the nation, its expensive housing market badgers much of the population.

More low- and middle-income housing is needed to ease the burden on the majority of Californians’ wallets. The additional supply will ease housing costs, allowing residents to both participate in the local economy and, for those qualified, save up for a down payment to become homeowners.

The good news is politicians can fix this aspect of the problem, and it goes beyond the presidential candidates’ sweeping national plans. A more direct solution to free up regional economies involves directing local governments to loosen zoning regulations, particularly in those areas with rapidly rising housing costs. The result will be beneficial not just to renters, but to real estate agents, who will see an increase in sales volume. The economy as a whole will improve as renters and homebuyers alike are able to contribute more of their paychecks to purchasing.

Otherwise, change will happen on the local level. In San Francisco, local residents are already taking on low-density housing regulations to improve access to rental housing and cool down rising rents. Forward-looking real estate agents may consider joining forces to allow more building in their own communities.

Yes.. the government easing regulations should cure all are ills, while GDP on paper in California may look good, only because of of stimulus monies set aside for special interest contractors. My opinion is we are ready to implode. Mind as well throw solar in the tech and science euphoria. As to why our GDP is growing has to do with printed money with zero backing! Did I say zero? Yes zero… maybe we can get the evil wealthy to pay more of their fair share, as if 90% isn’t enough for our social dictatorship …