Breach of a lease agreement and space vacated

Consider a tenant who breaches a commercial lease agreement before the lease expires and vacates the premises without the landlord’s service of a three-day notice to quit on the tenant. [See RPI Form 552 and 577]

The landlord may respond by taking possession in one of four ways:

- terminate the tenant’s right of possession and cancel the lease agreement by a surrender, then take possession and relet the premises to others or occupy the premises as the owner [See RPI Form 587];

- terminate the tenant’s right of possession using a three-day notice containing a declaration of forfeiture (or a notice of abandonment), take possession and relet the premises to mitigate losses before making a demand for payment of future rents [See RPI Form 575 and 581];

- take possession of the premises and relet it on the tenant’s behalf, then collect any monthly losses from the tenant; or

- enforce any tenant-mitigation provision in the lease agreement, leaving possession with the tenant to relet the premises to mitigate the tenant’s losses.

A critical distinction exists. Only ownership of a real estate interest, such as a leasehold interest, and personal property may be forfeited. However, a contract, such as a lease agreement, is not property. A contract is evidence of rights and obligations. Thus, it may be cancelled, but it cannot be the subject of a forfeiture. [See RPI e-book Real Estate Property Management, Chapter 31]

Related article:

Surrender as including a cancellation

A surrender occurs when:

- a tenant breaches a lease or rental agreement and vacates or intends to vacate the premises; and

- the landlord agrees to accept a return of possession of the premises from the tenant in exchange for cancelling the lease agreement.

The cancellation of the lease agreement in a surrender situation occurs by either:

- mutual consent of the landlord and the tenant [Calif. Civil Code §1933(2)]; or

- operation of law, implied due to the conduct of the landlord.

Editor’s note — Avoiding an unintentional surrender is one of the many reasons why a landlord needs to understand the difference between terminating a right of possession (the forfeiture of possession aspect) and the separate act of terminating a lease agreement (the cancellation of the right to future rents).

For a landlord to avoid adverse legal consequences when a tenant prematurely vacates, lease agreements contain a remedies provision stating a surrender occurs only when the tenant enters into a written cancellation and waiver agreement. [See RPI Form 552 §2.4; See RPI Form 587]

Surrender by mutual consent

Consider a tenant who makes a written offer to surrender the leased premises to the landlord.

The landlord believes a new tenant, who will pay more rent for the space than the current tenant, can be quickly located.

Still, the landlord demands an early-termination fee equal to three months’ rent to cancel the lease agreement. The tenant pays the fee and delivers possession, and the acceptance by the landlord cancels the lease. Here, a surrender has occurred. [See RPI Form 587 §2.2]

Editor’s note — Mid-term leases sometimes contain an early-termination provision for a surrender. The provision allows the tenant to cancel the lease agreement in exchange for payment of a termination fee. This fee usually is in the amount of two to six months’ unearned rent. This is a type of prepayment bonus or liability limitation provision seen in mortgages and purchase agreements.

Under an early termination provision, a surrender functions like a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure that conveys the real estate to the lender (possession returned to the landlord) in exchange for the lender’s cancellation of the note obligations (cancellation of the lease agreement).

Related Client Q&A:

Surrender by operation of law

Now consider a tenant under a lease with a ten-year term. A few years after entering into the lease agreement, the tenant vacates the premises. The tenant removes all of their personal property and returns the key to the landlord. The tenant has no intention of returning and breaches the lease agreement by paying no further rent.

Since a surrender cancels the landlord’s right to future rents due under the lease agreement, the landlord refuses to agree to the tenant’s return of possession.

To initially avoid a surrender, the landlord promptly informs the tenant they intend to enforce collection of future rent due by the terms of the lease agreement.

Then, without prior notice to the tenant declaring a forfeiture of the tenant’s right to possession, the landlord retakes possession, refurbishes the vacated space and leases it to a replacement tenant as the owner.

The new lease agreement with the replacement tenant is for a lower rent rate than the prior tenant owes under the breached lease agreement. The landlord notifies the prior tenant they have leased the premises to mitigate the tenant’s liability for unpaid rent.

The landlord makes a demand on the prior tenant for the payment of rent.

The rent demanded by the landlord is the difference between:

- the total amount of rents remaining unpaid over the remaining unexpired term of the prior tenant’s lease; and

- the amount of rent to be paid during the same period under the new lease by the replacement tenant.

Can the landlord recover the lost rent from the prior tenant who vacated the premises and returned possession to the landlord?

No! Before entering the space to prepare for reletting the premises, the landlord expecting to collect lost rent under the breached lease agreement must:

- terminate the tenancy by serving a three-day notice with a declaration of forfeiture (or a notice of abandonment); or

- notify the tenant they are taking possession of the premises as an agent acting on the tenant’s behalf.

The conduct of the landlord at the time they unilaterally took possession to relet the premises violated the tenant’s unforfeited and continuing right of possession. Although the landlord did not intend to accept a surrender, they did effect a surrender by taking possession without first forfeiting the tenant’s leasehold (or advising the tenant of the landlord’s intent to act on the tenant’s behalf to relet the premises).

Here, a surrender occurred by operation of law due to the landlord’s conduct. The landlord took possession while the tenant still retained their possessory interest in the property as granted by their lease agreement.

Thus, the landlord’s interference with the tenant’s remaining right of possession constitutes an acceptance by the landlord of an implied offer to surrender initiated by the tenant vacating the premises.

The result is the tenancy is terminated and the lease agreement cancelled by surrender. This result is avoided when the landlord first serves notice terminating the tenant’s right of possession with a declaration of forfeiture provision. [Dorcich v. Time Oil Co. (1951) 103 CA2d 677]

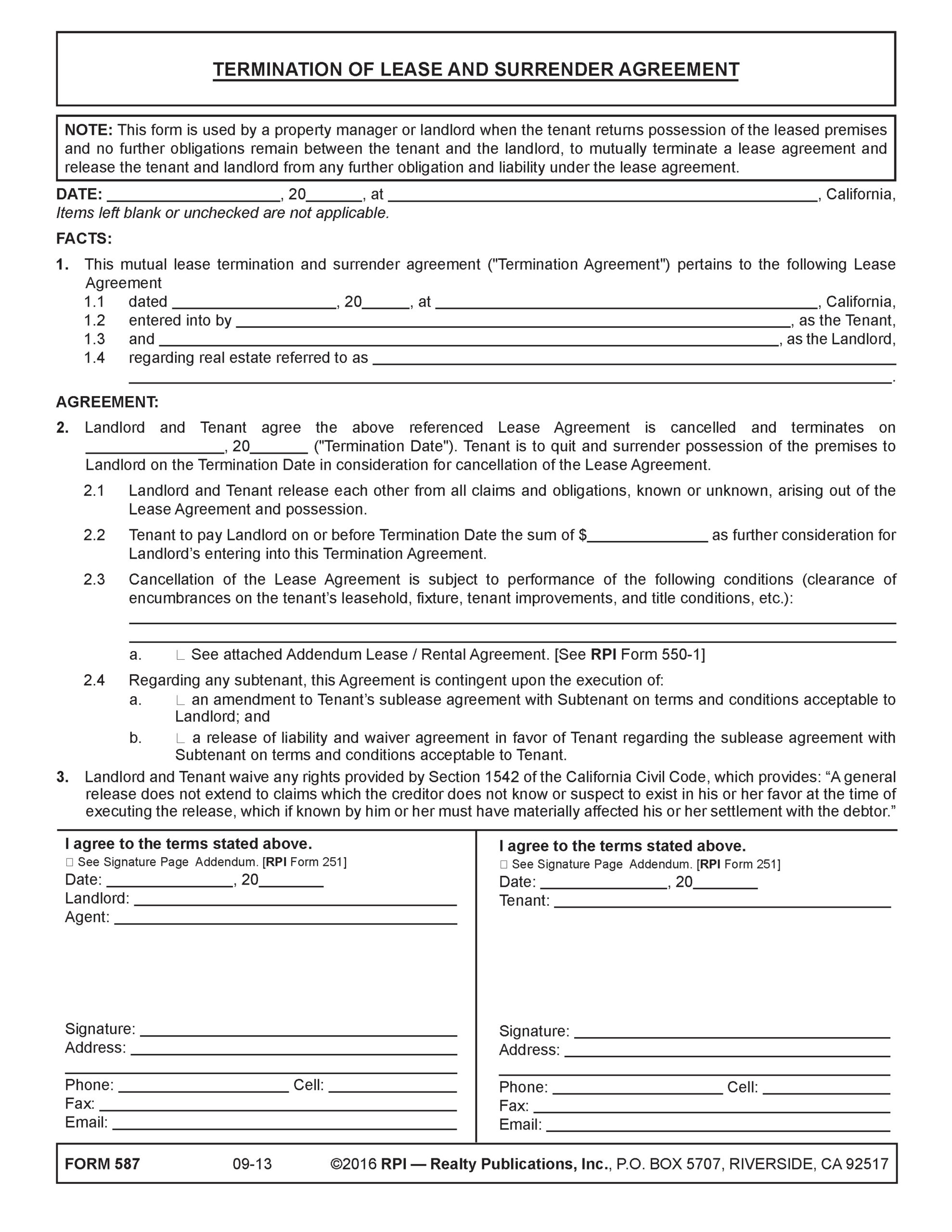

The termination of lease and surrender agreement

A property manager or landlord uses the Termination of Lease and Surrender Agreement published by Realty Publications, Inc. (RPI) when the tenant returns possession of the leased premises and no further obligations are intended to remain between the tenant and the landlord. The form allows the property manager or landlord to mutually terminate a lease agreement and release the tenant and landlord from any further obligation and liability under the lease agreement, no matter the type or timing of a claim. [See RPI Form 587]

The Termination of Lease and Surrender Agreement includes:

- the termination date on which the tenant is to quit and surrender possession of the premises to the landlord [See RPI Form 587 §2];

- a release between the landlord and tenant from all claims and obligations, known or unknown, arising out of the lease agreement and possession [See RPI Form 587 §2.1];

- any monetary consideration remaining to be paid by the tenant to the landlord [See RPI Form 587 §2.2];

- a description of any conditions to be performed prior to cancellation, which may include any payment the landlord will make to the tenant, such as a return of deposit, prepaid rent or settlement money on a dispute [See RPI Form 587 §2.3]; and

- conditions pertaining to a subtenant, when applicable, that needs to be arranged and agreed to. [See RPI Form 587 §2.4]

Related article:

Temporary displacement

A tenant in a community apartment project or a homeowner in a common interest development (CID) is to receive at least 15 days but no more than 30 days written notice when the management or Homeowners’ Association (HOA) needs the occupant to vacate the project in order to treat the premises for termites. [CC §4785(b)]

Condominium projects and planned unit developments (PUDs) are examples of CIDs.

However, when a landlord needs to temporarily displace a tenant who is occupying a unit not in a CID, discretion is needed to avoid violating the tenant’s right to quiet enjoyment to possession of the property. [CC §1940.2(a)]

Mutually agreed-to terms need to be set out in writing by the landlord and tenant when the landlord needs to conduct extensive repairs or fumigate a property requiring temporary displacement.

Unless otherwise agreed, the landlord is responsible for the tenant’s costs of temporarily relocating, including:

- hotel costs;

- pet boarding;

- meals when a kitchen at the replacement accommodation is not provided; and

- any other cost and expense incurred due to the displacement.

Related article:

Letter to the editor: Does temporary relocation due to repairs remove a tenant’s right to reoccupy?

The notice of temporary displacement

A property manager or landlord uses the Notice of Temporary Displacement published by RPI when invasive repairs or fumigation work require the temporary move-out of a tenant. The form allows the property manager or landlord to notify the tenant of the conditions for the temporary displacement. [See RPI Form 588]

The Notice of Temporary Displacement sets forth:

- the date and time by which the occupant needs to temporarily vacate the premises [See RPI Form 588 §2];

- a description of the work to be performed [See RPI Form 588 §3];

- the date and time the occupant may reoccupy the premises [See RPI Form 588 §4]; and

- the compensation offered by the landlord for the tenant’s temporary displacement. [See RPI Form 588 §6]

Related article:

Want to learn more about cancelling a lease agreement? Click the image below to download the RPI book cited in this article.