Energy-efficient improvements

Turbine Wind Farms

Most of a household’s energy consumption is spent on heating and cooling the home. To offset the cost of these energy demands, a homeowner can install his own small wind farm to provide energy needs for heating and cooling. Constructing your own wind farm is economically feasible only if your home includes:

- an area with frequent 10-mph (or more) winds; and

- an electricity cost of at least 10 cents per kilowatt-hour.

However, acquiring a building permit is a bit more difficult, as many communities resist change and will not allow wind turbines to be erected since many citizens see them as too ugly to be of general benefit.

Solar Panels

California leads the nation in the residential use of photovoltaic panels to generate clean electricity. Solar water heaters require a few solar panels on the roof of a building and even work in the chilly temperatures of Northern California. Hawaii has made panels mandatory in the construction of new homes, though there is no indication California will follow suit.

Geothermal

Using the Earth’s constant natural heat to warm and cool our homes is one of the most reliable energy-efficiency methods, and is available on almost any property with outdoor space to place the heat pump. A geothermal heat pump consumes 25%-50% less electricity than conventional heating and cooling systems now used, but costs roughly twice as much to install. While the cost may give homeowners cause to hesitate, geothermal proponents claim the quick payback time and minimal maintenance expenses compensate for the initial costs.

Using the Earth’s constant natural heat to warm and cool our homes is one of the most reliable energy-efficiency methods, and is available on almost any property with outdoor space to place the heat pump. A geothermal heat pump consumes 25%-50% less electricity than conventional heating and cooling systems now used, but costs roughly twice as much to install. While the cost may give homeowners cause to hesitate, geothermal proponents claim the quick payback time and minimal maintenance expenses compensate for the initial costs.

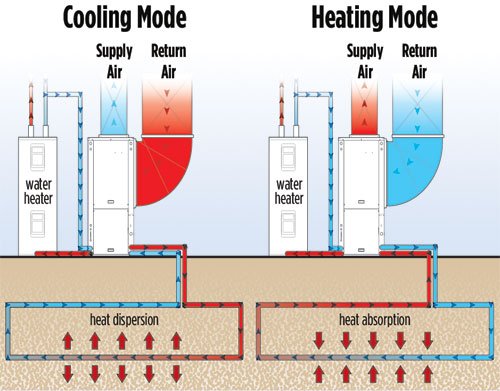

The geothermal pump is very similar to a regular heat pump, but instead of drawing heat from the air, it draws heat from the ground. Installation requires an outdoor unit and an indoor unit to transfer the ground temperature from the earth into the house. The geothermal pump works much like a cave; the air underground stays a constant, cooler temperature than the outside during the summer, and warmer than the air outside during the winter.

In the winter, the pump will move the relatively higher level of ground temperature from the earth into the home, warming it. In the summer months, the pump will pull the lower ground temperature from the earth into the home, cooling the home.

Ground heat is far more efficient since soil temperatures, even only a few feet underground, stay relatively stable all year round.

Tax Benefits of Energy Efficient Improvements

The government encourages homeowners to make energy-efficient improvements to existing homes by providing hefty subsidy tax rebates to help cover the costs of these high-priced improvements. California homeowners can receive up to $12,500 from the state for installing wind turbines, and an additional subsidy equal to 30% of the costs through federal income tax credits.

California’s solar water heater rebate program is a $350 million subsidy which pays homeowners up to:

- $1,875 to swap out their old natural gas water heaters; and

- $1,250 to swap out old electric ones when they install a solar water heater system.

The federal government also offers an additional 30% renewable-energy tax credit to homebuyers who install solar water heaters.

The state does not offer rebates on geothermal energy efficient improvements. However, the federal government offers a 30% subsidy by a reduction of the owner’s federal income tax liability via a tax credit.

California is also offering a state rebate program for purchasing energy efficient appliances. By trading in their old electricity guzzling appliances, California residents can get one of the following rebates:

- $50 for room air conditioners;

- $100 for clothes washers;

- $200 for refrigerators;

- $50 for freezers;

- $100 for dishwashers;

- $100 to $750 for water heaters; and

- $200 to $1,000 for heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

To collect their rebates, Californians need to mail in their rebate applications within 120 days after purchasing a qualifying energy-efficient appliance.

California is keeping up the PACE

The Golden State is getting on board the green bandwagon by persuading California homeowners to make energy-efficient improvements. The present depressed economy is a major hurdle for implementing the state government’s green plans, as many homeowners are unable or unwilling to make these improvements on their own. The state’s flagship plan is the named the CalforniaFIRST (CAFIRST) Pilot Program, a Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) financing program.

PACE was first put into action by the city of Berkeley in 2008, and is now implemented in sixteen counties and over 120 cities through the CAFIRST Pilot Program. The PACE program authorizes local governments to borrow money through the issuance of improvement bonds. In turn, the city loans that money to local homeowners to cover the upfront costs of the energy-efficient upgrades. Without putting any money into the improvements themselves, a homeowner can finance 100% of the energy-efficient improvements by borrowing money to cover the costs from a local agency who receives funds by issuing the improvement bonds.

The minimum loan amount for a single family residence (SFR) is $5,000, with a maximum of $75,000. The borrowed amount can be repaid in five to 20 years. The interest rate charged is a function of the rate bondholders are getting for the improvement bonds the local agency issued. The loan for the improvements is secured by the property. The loan documents do not contain a due–on clause, thus making the bond assumable by the buyer on a resale — if the new purchase-assist lender will accept a junior lienholder position, which at present is doubtful without some rethinking and recalculating in the secondary mortgage market.

The PACE loan, as a property improvement assessment, becomes a first mortgage on the property, junior to the property tax liens, but is legislated as senior to any trust deed loans encumbering the property. The lender most likely will not approve a loan on the house subject to PACE financing, since the senior lien is not a tax. It is an interest-bearing, amortized debt with a principal balance which reduces the homeowner’s equity in equal amount. These improvement assessment mortgages are deceptively entitled “special property tax assessments” since the method for payment and the collection is through the county tax collector’s office.

Improvements qualifying for the PACE loan include items such as:

- air;

- sealing;

- wall and roof insulation;

- energy-efficient windows;

- tankless water heaters;

- photovoltaics (solar electricity); or

- low-flow toilets.

Under the CAFIRST program, PACE loans have been funded with $16.5 million through the California Energy Commission’s State Energy Program. These funds are now available in 14 participating counties, including:

- Monterey County;

- San Luis Obispo County;

- Solano County;

- Alameda County;

- Sacramento County;

- San Mateo County;

- Ventura County;

- Fresno County;

- San Benito County;

- Santa Clara County;

- Yolo County;

- Kern County;

- San Diego County; or

- Santa Cruz County.

The funds are grants, designed to offset homeowner’s start-up costs and provide local education, outreach and an interest-rate buy-down for early participants. It is estimated that the CAFIRST will save the annual energy use equivalent of 10,600 average California households. Over the next two years, as CAFIRST becomes fully implemented, the program is expected to create approximately 2,000 new jobs.

Currently, the PACE loan program is on hold. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are in a battle with California bureaucrats over whether lenders can deny home loans for PACE participants. [For more information, see the July 2010 first tuesday article, Fannie and Freddie can’t keep up the PACE.]

The future of energy-efficiency and consumption

Energy consumption is no longer the soap box topic of a liberal agenda or the green movement, but has come to be recognized as a legitimate societal concern. With both the state and federal governments financially encouraging homeowners to lower monthly homeownership expenses with energy-efficient solutions, even the most fiscally conservative individual can see the advantages of energy-efficiency over older heating and cooling methods. Will conservative lenders and equally old-fashioned community politics voluntarily take the necessary action to get behind the trend, or will we have to look to legislation to guide and preempt our way out of past behavior?