Real estate licensees, bank representatives, economists, financial planners and business students gathered at the annual Inland Empire Economic Forecast Conference, held at the Riverside Convention Center on November 9, 2010, to discuss the economic recovery of Riverside and San Bernardino counties, California and the nation as a whole.

Hosted by Beacon Economics and the University of California, Riverside (UCR), the conference invited economists and local business leaders to present regional forecasts and propose community efforts to improve the image and sustainability of the Inland Empire.

Chris Thornberg, founding principal of Beacon Economics, opened the conference with his answers to the following pressing economic questions confronting California.

Is the recession really over?

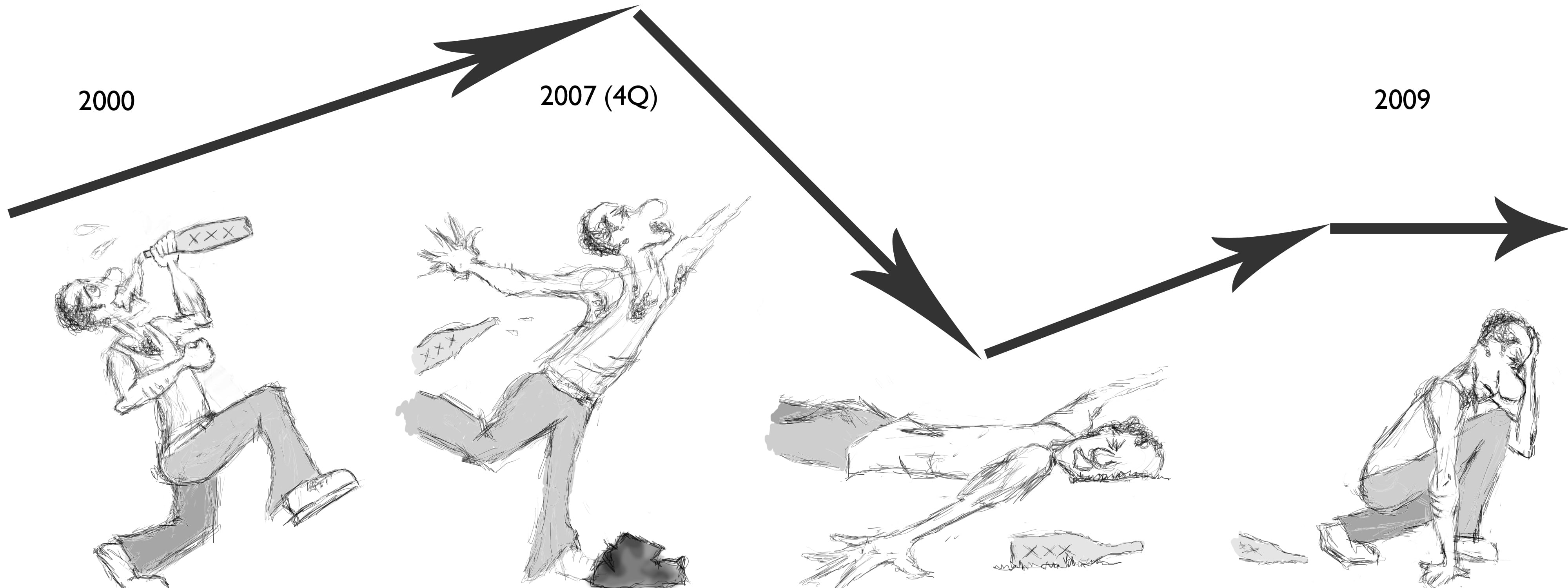

Thornberg answered with a definitive “yes,” but proceeded to explain the end of the Great Recession does not mean a return to the excess and artificial optimism enjoyed during the Millennium Boom – rather, the recession officially ended when the national economy stopped contracting in the end of June 2009.

He likened the overconsumption leading up to the recession to an economic intoxication, which inevitably led to a crash. The early stages of recovery, which we are presently experiencing, are not going to be pretty for quite some time — just as one must suffer through a hangover before returning to sobriety.

Thornberg and Beacon predict a slow recovery for at least another two years, with foreclosures and consumer weakness remaining strong perpetuators of the economic downturn.

What about California specifically?

Thornberg described the high volume of housing and exports as factors that contributed to California’s particularly arduous financial crisis when compared to the rest of the nation. California is a state of extremes: we feel the euphoria of boom times more poignantly than the rest of the country, though we also experience the sting of recessionary periods more acutely.

Much like a caricature, California’s economy is a hyperbolic representation of the nation at large, with periods of national economic extremity unmistakably reflected in California’s markets at even bleaker levels. The Great Recession was no exception, and the consequent return to stability will likely be less handsome in California than in other states.

What can we do to stimulate recovery?

A focus on the construction of more housing near mass transportation hubs and employment centers will support the recovery, states Thornberg in his Beacon analysis. Vast amounts of population growth in California are attributed to immigration — a demographic that needs housing close to their jobs.

The most important thing California can do is be patient. Thornberg acknowledged California is already healing, and pointed to continued future population growth and budding first-time homeowners who will soon be economically capable of purchasing property (once they find employment) as hopeful and important remedies to this convalescing market. It will also take time for current homeowners to rebuild the massive amount of equity that disappeared from their properties after the Millennium Boom.

Thornberg’s assessment of economic stimulus was punctuated by an implicit wariness of government intervention. He characterized government efforts to stimulate the economy as ill-conceived attempts to force the invisible hand of the free market, a signal example being the Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) recent quantitative easing — the process of buying trillions of dollars worth of Treasury bonds in order to further drive down consumer interest rates and dramatically increase the money supply.

According to Thornberg, government policies such as quantitative easing only serve to delay economic recovery by reducing the severity of the crash while drawing out the rebound. The promise of instant cash in the consumer pipeline may spur lending and consumer spending in the short term, but the excess cash injected into circulation will have to be balanced eventually by indications of a truly organic recovery: increased gross domestic consumption (GDC) and a diminishing national debt.

The hangover resulting from the binge/purge excesses of the Great Recession will not last forever. The current economic cycle is following a historic pattern that will result in more signs of impending recovery in another few years – and we must be patient until we get there.

first tuesday take: Our forecast for the recovery of the California housing market has been “in your face” for over a year, and we still place California’s real estate recovery a bit further in the distance than Thornberg’s most optimistic view, but consistent with his overall economic viewpoint. The end of the recession is expressed on national terms and has little to do with California, as we are not yet at the bottom of our regional recession which, it seems, will be in the first quarter of 2011 – Orange County presently in the lead.

Even this good news does not mean we are out of the woods – we’re just not sinking unabated as we were before the current touchdown and unemployment bottom. It is from this point that the California real estate recovery will stand fully on the strength of any employment increase we can muster.

California home prices will not fully stabilize until 2014, with prices increasing into a peak around 2018 as Generation Y matures into a vast demographic of first-time homebuyers. The return to the peak prices of January 2006 will not happen again until around 2025 – believe it and implement your investment plans around it, as any lost cash (and equity) in current property values is an unrecoverable “sunk cost”. [For more information regarding price peak predictions, see the October 2010 first tuesday article, Another prediction that California metro area price peaks won’t return until 2025.]

The California economy is still queasy from the overbuilding which occurred during the Millennium Boom. The number of new housing units built in 2005 spiked to 155,000 and then dropped to a measly 25,000 in 2010 — a sure sign of excessive building when times were good and cash in the form of mortgage financing was plentiful. Construction is currently one of the industries hit hardest by unemployment as there are enough existing homes (and vacant apartments) already built to meet housing demands alongside resales for the next three to five years and no more are needed until this surplus is reduced. [For more information regarding California homebuilding, see the September 2010 first tuesday article, Weakened homebuilding industry not part of California recovery.]

Much like Beacon Economics, we at first tuesday look to the coming Generation Y demographic as an influx of new homeowners who will help clear out the inventory of vacancies and pull us out of this real estate quagmire. Until the price bump in 2018, Californians must be patient and agents must focus on preparing themselves to serve the new demographic of homebuyers in a more prudent spending climate anchored in fundamentals. Investment in income-producing real estate to hold as a collectible for years to come needs to be the current search, but the time to actually buy at the best prices and on seller carryback terms is yet to come. [For more information regarding the future buying power of Generation Y, see the October 2010 first tuesday article, The demographics forging California’s real estate market: a study of forthcoming trends and opportunities.]

Re: Beacon Economics