Facts: An owner of improved residential property and undeveloped land took out a loan secured by a trust deed encumbering both. In the event of default, a trust deed provision called for the properties to be sold at foreclosure in any order. However, the lender verbally assured the owner the undeveloped land was to be sold first if foreclosed. The owner defaulted on the trust deed and the lender foreclosed on the residential property first.

Claim: The owner sought to pursue their money losses for wrongful foreclosure from the lender, claiming the lender engaged in unfair business practices since it foreclosed on the residential property first after verbally promising the owner it would, on a default, foreclose on the vacant land first.

Counterclaim: The lender claimed it had not engaged in unfair business practices since the terms of the trust deed stated the properties were to be foreclosed and sold in any order.

Holding: A California court of appeals held the owner may not pursue the lender for money losses since a provision in the trust deed securing the loan stated the properties were to be foreclosed on in any order determined by the lender. [Wilson v. Hynek (2012) 207 CA4th 999]

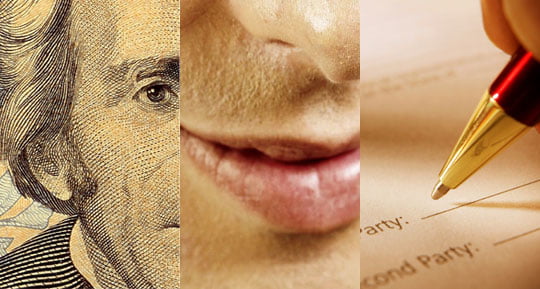

You can’t hold a lender to their word

This case is yet another warning to borrowers about “promise-them-anything” lending: never rely on a lender’s spoken word. Unless you believe in the fantastical tooth fairy, lending is an asymmetrical power relationship, not one of a willing lender and a willing borrower sharing a common goal and rooted in mutual consent. Remember, the interests of the lender and borrower are at opposite ends of a financial teeter-totter — they are diametrically opposed. It is a relationship of polarities: rentier and debtor.

The rigged lending-game requires borrowers to rely solely on the lenders’ verbal assurances and proposals to get a mortgage. Conversely, the lender bears no burden and suffers no consequences for failure to follow through on any of their oral or unsigned written promises.

Always get it in writing

Consider an owner planning to make improvements to their industrial property. The owner applies for a mortgage to upgrade the facilities, add equipment and construct additional improvements. The owner has a long-standing business relationship with the lender, having borrowed from it in the past.

The loan officer processing the mortgage orally assures the owner it will provide permanent long-term financing to refinance the short-term financing the owner will use to fund the improvements. Nothing is put to writing or signed. Relying on the lender’s oral assurances, the owner enters into a series of short-term loans and credit sales arrangements to acquire equipment and improvements.

The loan officer visits the owner’s facilities while improvements are being installed and constructed. The lender orally assures the owner they will provide long-term financing again.

On completion of the improvements, the owner makes a demand on the lender to fund the permanent financing. However, the lender refuses. The owner is informed the lender no longer considers the owner’s business to have sufficient value as security to justify the financing.

The owner is unable to obtain permanent financing with another lender. Without amortized long-term financing, the business fails for lack of capital. The business and property are eventually lost to foreclosure by the short-term financing lender. The owner seeks to recover money losses from the lender, claiming the lender breached its commitment to provide financing.

Can the owner recover for the loss of their business and property from the lender?

No! The lender never entered into an enforceable loan commitment. Nothing was placed in writing or signed by the lender which unconditionally committed the lender to specific terms of a loan. [Kruse v. Bank of America (1988) 202 CA3d 38]

And always get it signed

Consider another property owner in default on their mortgage. The owner is in negotiations with the lender to modify the mortgage.

The lender sends the owner a mortgage modification agreement. However, the agreement is unsigned by the lender and payment calculations in the document are incorrect. The owner notices these errors and contacts the lender.

The lender instructs the owner to cross out the incorrect information and enter corrections, sign the agreement and send it to the lender with the down payment that it calls for. The lender assures the owner the agreement will be corrected and finalized. The agreement bars a foreclosure if the owner follows all the terms of the agreement.

The owner sends the down payment and the signed agreement with the noted corrections to the lender. The owner fully performs all obligations under the modification agreement. However, the owner never receives a copy of the corrected agreement with the lender’s signature.

Later, the lender files a notice of default (NOD) and begins foreclosure proceedings. The owner seeks to stop the foreclosure, claiming the mortgage modification agreement is enforceable since the owner followed all the terms dictated by the lender.

Is the agreement enforceable?

No! The mortgage modification agreement is not enforceable. Here, the lender never signed the written agreement they had orally agreed to. Even though the lender prepared the written agreement, orally assured the owner about its terms and accepted the owner’s down payment, the agreement signed by the owner was not also signed by the lender. Thus, the agreement was always oral, and in turn unenforceable, due to the requirements of the statute of frauds calling for a writing signed by the person or entity who is charged to perform. [Secrest v. Security National Mortgage Loan Trust (2008) 167 CA4th 544]

Written word > spoken word

Under the statute of frauds, the following transactional agreements need to be evidenced in a writing signed by the person charged to perform to be enforceable:

- the sale of real estate;

- broker employment agreements [See first tuesday Form 505 and 506];

- a lease agreement with a term exceeding one year;

- escrow instructions [See first tuesday Form 401];

- any loan secured by a trust deed; and

- any loan commitment not secured by a trust deed which exceeds $100,000. [Calif. Civil Code §1624]

Typically, most of these types of transactions are reduced to writing to conform to the dictates of the statute of frauds, except for mortgage commitments situations. In these scenarios, the written word controls, despite verbal representations to the contrary made by any of the parties.

Moreover, mortgages of any dollar amount are required to be entered into in a signed writing. Thus, until all mortgage documents have been signed by the borrower and the lender, disregard any verbal or written but unsigned promises by the lender. They’re as substantial as smoke and mirrors.

It is common for lenders to promise low rates, charges, mortgage amounts and advantageous funding timetables to induce a borrower to apply for a mortgage. Lenders document these promises in writing, but frequently without a signature. When the time comes for the lender to fund and close, the lender unapologetically explains markets rates and costs have gone up. Here, the borrower cannot enforce the lender’s promises. [Calif. Civil Code §1624]

Relying on the final mortgage commitment

The only communication with a lender that matters in the mortgage process is what the lender ultimately does when the time comes for funding.

Further, the only writing that counts and may be relied upon is the final mortgage commitment on single-family residence (SFR) mortgages delivered three days before closing, and the trust letter at closing instructing escrow when and how to use the funds the lender has forward. [CC §2922]

Thus, the lender-borrower relationship is one of power, not one of an open market arrangement.

Related reading

Rate locks: tin shields or the real deal?

Enforceable agreement to grant a permanent modification

Now consider a lender who signed a Servicer Participation Agreement with the U.S. Department of Treasury under the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP). The lender agrees to follow the Treasury’s guidelines and procedures in modifying mortgages.

A distressed-homeowner applies to the lender for a modification of their mortgage. The lender prepares a written Trial Period Plan (TPP) which states the homeowner will receive a permanent mortgage modification if they make trial modification payments and submit qualifying documents.

The borrower signs the TPP and returns it, makes all trial modification payments and submits the required documentation to confirm eligibility for the permanent modification.

The lender never agrees to give the homeowner a modification nor do they notify the borrower of any failure to qualify. However, under HAMP, the lender is contractually obligated to provide a modification when the homeowner meets all the requirements under the TPP. The homeowner seeks to compel the lender to grant a permanent modification since they followed all the terms of the written TPP.

Is the lender compelled to grant a permanent modification?

Yes! The borrower followed all the terms of the written TPP, and thus the lender was compelled to grant the permanent modification since they had signed the Servicer Participation Agreement under HAMP. [Corvello v. Wells Fargo Bank (9th Cir. 2013) 728 F3d 878]

Related reading

The problem with HAMP

Thus, once a lender signs a written agreement, they are bound to follow it. This commitment is the reason lenders rarely enter into signed written promises regarding a mortgage application. Nothing is signed by the lender which is enforceable except for the final three-day mortgage commitment and their conditional delivery of mortgage funds to escrow.

Lenders do not become obligated to make a mortgage, until they have funded and the documents recorded – none of which are signed by the lender.

Written agreements are a two-way street

Consider a broker who arranges a mortgage for a property owner, funded by a private money lender. The borrower signs the note and the lender provides the funds.

The lender is structured as an entity and is solely owned by the broker. The broker does not receive a broker fee and none is paid on the mortgage transaction. The note carries an interest rate greater than the legal threshold set by usury limitations.

The owner defaults on the trust deed and the lender forecloses. The borrower seeks to invalidate the foreclosure, claiming the interest earnings violated usury limitations on mortgages.

Is the foreclosure valid when the interest rate exceeded usury limitations?

Yes! Here the loan is exempt from usury limitations since a licensed broker arranged the loan and received compensation as the owner of the lender. The borrower agreed to the interest rate on signing the note, and that note is enforceable by foreclosure under the trust deed securing the debt owed. [Bock v. California Capital Loans (2013) 216 CA4th 264]

Just as lenders are held to signed written agreements, so are borrowers. Courts resist invalidating written agreements entered into by a lender and borrower if they can find a basis for enforcing them. Thus, any borrower hoping to avoid performing on a signed written mortgage agreement has an uphill battle — one they are unlikely to win.

Agents provide protection for their buyers

Agents and brokers, the professional gatekeepers to the entry of real estate, know the deceptive practices lenders use to take advantage of borrowers. Thus, they are equipped with knowledge and experience to come to the aid of their client when dealing with lenders.

Related reading

Lenders vs. owners and the real estate interest of each

In order to prepare a buyer for the mortgage application process, agents need to advise their buyer of the likely scenarios they will encounter in the mortgage application process. Again, the relationship between lender and borrower is inherently adversarial. Thus, the informed buyer is best able to anticipate and defend themselves when confronted with unscrupulous eleventh-hour lender tactics.

Always advise buyers seeking a purchase-assist mortgage to “double app;” that is, submit mortgage applications to a minimum of two lenders as recommended by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the California Bureau of Real Estate (CalBRE). Multiple competitive applications keep lenders vying for your buyer’s business up to the very last minute – the ultimate moment of funding, when commitments truly are commitments.