Rising home values have an adverse effect on college attendance, according to a recent study appearing in the Economist. A correlation exists between booming housing markets and decreased college turnout.

The authors of the study reason that when home values rise rapidly, other sectors of the economy are also booming, including jobs and incomes. Therefore, recent high school graduates are more tempted to skip college and head straight to the job market, where they can make a quick buck.

However, the study was limited to the 2000s, during the overblown Millennium Boom of home prices and economic excess. Of course college attendance decreased during this time — consumer confidence was through the roof and the cyclical unemployment rate during the 2000s was extremely low.

Then, following the housing and financial crash, the economy suffered a series of shocks and setbacks. Jobs became scarce for recent high school (and college) graduates. So many who would have otherwise skipped post-secondary education chose the only viable option: attend college or graduate school.

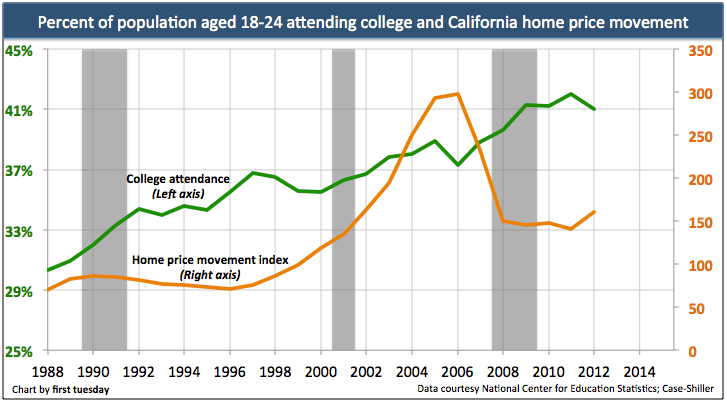

While fluctuating from year-to-year, college attendance has experienced a visibly rising trend for decades, as seen in the chart below. However, as the study notes, small dips occur during peak economic performance. For instance, there was a dip in 2005, during the height of the Millennium Boom. A similar dip is seen in 1998-1999, during the height of the dot-com bubble. Further, during each of the past three recessions (marked by gray bars on the chart), college attendance has increased.

People want to invest in their future. How they choose to invest depends on what options are available to them upon entering adulthood. When jobs are scarce, they invest through education and taking on student debt. When jobs are plentiful, they choose to invest in a home and community, via mortgage debt.

The stake for real estate

What does this information mean for real estate professionals?

The trend is undeniably up for college attendance, and brief dips during economic booms aren’t doing much to dampen this movement. This is, at its most basic level, good news for future economic and real estate performance. That’s because college-educated individuals earn more over a lifetime than their less-educated peers, thus more college-educated homebuyers will lend support to rising home values.

Then there’s the downside. During recessions, some individuals go to college or on to graduate study when they otherwise would not have. The inflated number of young people with master’s degrees in things like underwater basket weaving is kind of like those who bit off more than they could chew during the housing boom, when credit was easy and standards were low.

Young people who couldn’t find jobs during the recession instead took on large amounts of student debt. And, like those who over-extended themselves in the mid-2000s and suffered foreclosure, many of these over-educated individuals are likely heading for their own default crisis — this time due to student loans.

Student debt is currently hampering a generation of college grads, as the average student debt load is now nearly $30,000, and growing, according to the New York Federal Reserve. If an individual pays this back at the standard ten-year plan, they owe about $340 per month. That’s $340 less to put toward saving for a down payment, paying a mortgage or contributing to the economy.

Further, if they are on a reduced, income-based repayment plan (since underwater basket weaving doesn’t pay too well), they will be paying back their loans for — not ten — but twenty years. This pushes off homeownership significantly for those who have to pay.

Therefore, expect much of the next first-time homebuyer generation to remain renters until their 30s or 40s. It’s going to take them longer to save up and qualify for the mortgage they want and deserve with their higher level of education. Home sales volume will feel the absence of these young buyers for the next few years. But once they do enter the market, they will be well-armed with higher-paying jobs and more financial savvy than their Generation X and Baby Boomer parents. Except for those basket weavers, they’re pretty much screwed no matter what.